The Modocs were a small band of Indians, located on Lost River, Oregon. Lost River empties into Tule Lake, which lies partly in California and partly in Oregon. These Indians, numbering about seventy-five or eighty adult men capable of bearing arms, were camped near the mouth of the river, and bordering on the lake. They traded back and forth to Yreka, California, and many could speak a little broken English. So far as I could learn they were entirely peaceful, and, according to tradition, their ancestors for many generations had inhabited that region. This, however, was not included in the Indian Reservation; therefore this small band of Indians must be removed from the home of their childhood, the land of their ancestors, that the white man might possess it. To this the red men demurred and it was, therefore, decided to send Jackson’s troop of the First Cavalry from Fort Klamath, Oregon, by a sudden and stealthy march at night, surround them at daylight, and move them forcibly on to the reservation they hated.

To the Indian Department this apparently seemed an easy matter. How easy subsequent events show. Jackson made the attempt and appeared before the astonished Indians on the morning of November 29, 1872. The latter, evidently considering this treatment a declaration of war, opened fire upon the troops and then fled to the lava-beds. They had undoubtedly considered this emergency and were prepared for it.

The lava-bed was of irregular shape, estimated roughly to be thirty-five miles north to south and twenty-five east to west, and washed by Tule Lake on northeast and east side. In the lava-bed were a number of extinct volcanoes, all of which had at some time assisted in distributing this enormous amount of lava. Most of it was of a dark color about the same as the Indians, and appeared like a solid molten mass suddenly cooled. There were many caverns and fissures, undoubtedly known to the Modocs, as I shall hereafter designate these Indians. There was only one trail over which animals could be taken, traversing the lava-bed from northwest to southeast, but animals might be taken around the edge of the lake, although exceedingly rough. This scoria, or lava, had hardened in undulations or waves, some of them reminding one of the waves of the Atlantic on the Jersey coast, could they be caught and held rigidly as you observe them coming in, one after the other. These, as can readily be seen, formed admirable natural defenses, the Modocs retiring from one crest to another as the troops advanced, and invariably, from their concealed position, inflicting loss.

At this time I was stationed at Camp Warner, Oregon, about one hundred and fifty miles from the lava-beds. The news of Jackson’s fight and orders to proceed at once with my troop to his camp reached me by courier about December 2, 1872. Upon my arrival, I found Bernard with his troop First Cavalry already there, he having gone from Britwell, California. And Major John Green (affectionately designated by his younger officers as Uncle Johnnie), than whom no braver man ever wore the uniform.

By this time it became certain that we were confronted with no easy task, and troops were ordered in from all near-by garrisons, including about one hundred Oregon militia, reinforced by a major and a brigadier-general from the same State, who looked upon the whole affair as a sort of picnic. In the meantime, Bernard, with his own and Jackson’s troop, had been ordered to the south end of the lake to prevent the Modocs leaving the lavabeds by that route. Lieutenant-Colonel Wheaton (brevet Major-General) had arrived from Warner and assumed command and moved our camp from the mouth of Lost River to Van Bremmer’s Ranch, about ten miles farther west, as being more accessible, both as a rendezvous for troops and for supplying them, as everything had to be shipped via Yreka, California.

All being in readiness, it was decided to attack the Modocs on the 17th of January, 1873. Bernard was to move up the trail along the lake, leaving his horses in camp, and traveling at night, capture the Indian stock (ponies) grazing on the lake front. In this he was successful. After that and simultaneously with our attack of the Modoc position on the west, he was ordered to strike them from the east. What was afterward known as “Jack’s Stronghold” was near the lake and about midway between the east and west attacking points.

We moved out the afternoon of the 16th and made a dry camp that night about one mile from the bluff at the north end of the lava-bed. This bluff” was very steep and high, undoubtedly putting a stop to the further flow of lava in that direction; but by erosion there was quite a space grass-covered at the bottom, large enough to enable us later to put our whole command, much increased, in camp there. The command on the north side consisted of a battalion of infantry under command of Major Mason, my troop of cavalry, and the Oregon militia, the whole under command of Colonel Wheaton. We moved soon after daylight, the infantry taking the head of the column, the cavalry following, and the Oregon militia bringing up the rear.

Before the fight it had been a joke around camp that “there wouldn’t be enough Indians to go round.” As I stood on the bluff and gazed out above the lava-bed that morning, it conveyed the impression of an immense lake. A mist or fog hung over it, so dense that nothing transpiring therein was visible, while about us at the top of the bluff all was clear. To see the column go half way down and then disappear from view entirely was, to say the least, uncanny and might have suggested the words of Dante’s “Inferno,” “All hope abandon, ye who enter here.”

But I did not have time to indulge in fancies inspired by the sight of disappearing troops, as my turn to move soon came, closely following the infantry which deployed so soon as the descent was accomplished, their left vesting on the lake. I deployed my troop on the right of the infantry, and the militia in turn took position on my right. These dispositions had not been completed when the Modocs opened fire upon us, and the first man hit was a militiaman who was on the way to his position, passing in rear of my line. At the same time we could hear the reports from Bernard’s guns, showing that he was attacking as directed.

In this way we pushed or worked along for perhaps a mile, the men screening themselves as well as possible. No Indians could be seen; they, of course, were much scattered in order to contest the advance of our whole front, the troops being much more numerous than the Modocs. The Indians would lie behind the crest of the waves, before mentioned, their black faces just the color of the lava; and, after firing, retreat to some other crest, where the same thing was repeated. They never exposed themselves for an instant, and the first warning the troops would have of their proximity would be the cracking of rifles and the groan of a comrade, with perhaps a glimpse of curling smoke as the fog lightened.

Knowing as they did every crevice and fissure through which to escape detection after each shot, it can readily be seen what obstacles the troops had to overcome in order to make any progress at all. These conditions continued, with the exception of the fog, which gradually lightened and finally disappeared throughout all the fighting of that day in the lava-beds.

We made but little further progress, and being much annoyed by the fire directly in my front, I ordered a charge by that portion of my line most exposed to it, when greatly to my surprise I found running along my entire front an enormous chasm absolutely impassable, so far as I could ascertain. Just then some of my men called out that they had found a way down into the chasm, at which the men nearest broke to the right and left and entered this gorge. On joining them, I found that the Modocs had evidently anticipated this very move and prepared for it. They had it completely covered by their rifles, and had it not been for the fact that at the mouth of the gorge stood an enormous boulder, I and my party must have been annihilated.

To get out of our predicament I called to one of my men, who had been stopped at the entrance, to hurry to Colonel Green, explain the situation, and ask him to order the infantry to make a demonstration in front of the Indians, in hopes that it would relieve the pressure on my position. This was done and I got back to my line with comparatively small loss.

We were now close enough to Bernard’s right to call him, and found that he had made no greater progress on that side than we had on ours. By this time it must have been between one and two o’clock in the afternoon, and I heard Colonel Green, who was in command of the firing-line, call to Bernard that he was going to connect with his (Bernard’s) right. This meant moving by our left flank along the lake and in front of Jack’s Stronghold, which, of course, the Modocs would resist desperately as, in the event of our seizing it, they would be cut off from water. And this they did, and with such effect that our line, moving by the flank, was cut in two, part of my troop and the militia remaining on the west side. At this time the firing by the Modocs was so fierce and deadly that the whole command was forced to lie prone. I don’t remember any order to that effect. None was needed. And the Modocs held us there until darkness permitted our escape.

During all this day’s fighting I did not see an Indian, and I don’t recall that any one else did, though they called to us frequently, applying to us all sorts of derisive epithets. It was at this point that our greatest number of casualties occurred. I was wounded about four P.M., having raised myself upon my left elbow to look at a man who had just been killed. A shot at my head missed that, passed through my left arm and into my side.

That night we retreated to Bernard’s camp on the south side of the lake, about twenty miles from the scene of the fight, over a rough trail through the lava. General Wheaton, with the remnant of the command on the west side, returned to the main camp at Van Bremmer’s Ranch. Colonel Green was obliged to march around the east side of the lake, in order to join General Wheaton, and this he did with as little delay as possible. We who were wounded were sent to Fort Klamath, about a hundred miles distant, which we reached at the end of the third day.

It was now realized that to subdue the Modocs a much larger force would be necessary, and troops were rushed to the scene from all available points; but, before anything more could be done by the military powers, the Washington authorities decided upon a peace commission to treat with these Indians, a great mistake at this time, as any one should have realized the utter futility of attempting such a thing with a savage foe flushed with victory. After hostilities have actually begun, the only way to treat with an Indian is to first “thrash” him soundly, which usually has the effect of rendering him amenable to reason.

While these negotiations were being conducted my wounds healed, and I was permitted to rejoin my command at Van Bremmer’s Ranch, the date I am unable to state. Shortly after this General Canby, the Department Commander and President of the Peace Commission, concluded that it might have a better effect upon the Indians to inject a little display of force into their deliberations, so he moved his whole command into the lava-beds, Bernard taking up his old position on the east side, from where he made his attack January 17th, and we with all the other troops camping at the foot of the bluff heretofore described. Our signal-station was far enough up the bluff to command a view of everything in our front and communicate with Bernard.

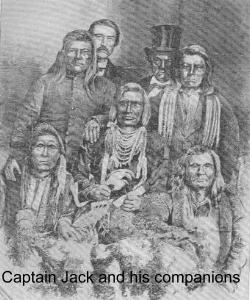

It was no unusual thing, when flagging to the other command, to see an Indian appear on the top of Jack’s Stronghold and mimic with an old shirt or petticoat the motions of our flags. From the signal-station close watch was kept on the tent where the Peace Commissioners were to meet Captain Jack and the other Modocs on that i ith of April, 1873. I neglected to state that, in the meantime, the command on the east side had been much strengthened and Major Mason given command.

Two or three days previous I had been detached to escort the body of a brother officer to Yreka, and returned the afternoon of the 11th, and at the top of the bluff heard the sad details of the massacre of the Peace Commission. . . . I have always thought, as these Indians could have had no animosity against General Canby, nor hoped to kill off all the soldiers, that they believed, if they could kill the Big Chief and incidentally as many of the lesser lights as possible, that, like a savage force whose leader had been killed, the balance would become demoralized, disintegrate and disappear. On no other theory can I account for such base treachery.

Of course all hopes or wishes for peace were now abandoned and preparations made for the coming struggle. The exact date I cannot recall, but think it was the 14th of April. I left camp at two A.M. with two troops of dismounted cavalry and three days’ cooked rations. I marched about half-way to Jack’s Stronghold and waited for the balance of the command, infantry and artillery, the latter as infantry, except a detachment that had a section of cohorn mortars. This command did not leave camp until eight A.M., and soon as they arrived were put into position much the same as January 17th, but this time, owing to our numerical superiority, we were able to make greater progress and by night had them closely pressed, though unable to dislodge them.

Then our cohorn mortars were put into position and dropped shells into their camp all night long at fifteen minute intervals. The firing by the Indians continued all night, and several times they tried to stampede our lines by fierce assaults; but in every instance without success, though their firing was incessant. The next day we succeeded in closing in a little more, and that night the mortars continued the same as the night before, viz: throwing shells into Jack’s camp every fifteen minutes, while the Indians continued firing more furiously than ever, accompanied by demoniacal yells which made the scene one never to be forgotten by those who heard it.

Just before daylight the firing by the Indians slackened, and about the same time some of our advanced lines were enabled to gain ground, and about ten o’clock we discovered that the stronghold had been abandoned. One reason was that we had cut them off from water, and, also, the mortars rendered their stronghold untenable. As I remember, by noon of the third day not a trace of an Indian could be discovered. They had vanished completely and were lost to us among the vast caverns of the lava-beds which they knew so well. During the three days just described our men were killed going back and forth to our camp, so that if anything was needed a large escort had to be sent.

The following extract from a letter of mine, written April 17, 1873, well describes our condition:

“The great event of the campaign has been accomplished, viz: the driving of Jack from his stronghold. The fact of our remaining on the line day and night convinced him that we had come to stay. The infantry and artillery are camped in the stronghold. Bernard and Jackson have gone around on the east side, while I go the west side of the lava-beds, so that in the event of the Modocs trying to get out, we can cut them off. I can’t write more to-night as I am very tired and have to be in the saddle at daylight. I have not washed nor combed my hair for three days. It’s no pleasant thing to live in the rocks for three days and two nights with now and then a bite of cold food, and an incessant fire on the line all the time.”

The cavalry as indicated above made the entire circuit of the lava-beds without finding any trace of the Indians, and close watch was kept in every direction to prevent their escape. No further fighting occurred until the 26th of April, but during the intervening time speculation was rife in camp as to the exact locality of the Modocs. That they had not left the lava-bed was certain. How they procured water was a mystery never solved satisfactorily. Once in a while a moccasin track would be reported and the locality closely watched, but no reappearance was ever reported.

On the 25th of April it was decided to make a reconnaissance into the lava-beds in an effort to locate the Indians. The command was to be composed of foot troops, infantry and artillery. Captain Thomas of the latter arm sought and obtained the command, consisting of sixty or seventy men and six officers, including the doctor, as follows: Captain Thomas, Lieutenants Howe, Cranston, Wright, Harris, and Dr. Semig. The command left camp at seven A.M., and about noon signaled back that they had struck the Indians. We could distinctly hear firing, and with a glass make out a portion of the troops. There did not appear to be any hard fighting, and everybody in camp supposed that Thomas could easily take care of himself, if unable to inflict any punishment upon the Indians.

About three P.M. some stragglers and wounded men made their way into camp and said the command had been ambushed and cut off. Colonel Gillem immediately despatched all the available men in camp under command of Colonel Green to the assistance of Thomas. I did not accompany the command, owing to trouble with my wound that interfered with my walking. We did not anticipate anything serious, but supposed Thomas had probably taken up a strong position, and waiting for darkness, would make his way back to camp. During that night quite a number of stragglers came in, and in the morning Colonel Green signaled that they had found the bodies of Thomas, Howe and Wright, Harris and Semig, the last two both wounded. Cranston they were unable to find. Colonel Green returned the morning of the 28th with the dead and wounded. They had been without sleep or rest for two nights and a day, part of the time in a pelting rain.

It now seemed that the only thing to do was to wait until, compelled by starvation, the Indians would be obliged to leave the lava-beds. There was no more fighting until the Indians struck Jackson’s command as they were leaving the lava, but of this I can give no account as to date or particulars of fight.

The events above narrated bring me to the capture of Captain Jack. When the Indians left the lava-beds, Colonel Green took up the pursuit with all the cavalry that he could quickly get together. My squadron being too far away, I did not participate. However, General Davis, who had succeeded General Canby in command of the Department, decided to move his headquarters to Applegate’s Ranch on the east side and in the direction the Modocs had taken. We had just gotten into camp at Applegate’s when the General sent me word that the Modocs had surrendered, but that Captain Jack and his family and a few followers had escaped, and for me to take my squadron and endeavor to effect his capture. I started at once and taking a few Warm Spring Indians, whom I knew to be good trailers, started to cut the main trail. This was some time after noon, and about sundown I struck one trail of Colonel Green’s command, and knowing that I could accomplish nothing by following that went into camp.

During the night I made up my mind that Jack intended going back to the lava-beds where he could conceal himself indefinitely, so at daylight I took the back track and before noon my scouts reported squaw tracks traveling in the same direction as ourselves. I have neglected to state that my squadron consisted of my own and Captain Trimble’s troop of the First Cavalry. About. the time that these tracks were reported we were marching parallel to a deep gorge that lay on our right and impassable for animals except at a few crossings, and, coming upon one of these, directed Trimble to cross to the opposite bank. Soon after my scouts sent me word that the tracks led into the ravine. I then deployed my company, under my lieutenant, and went ahead with my interpreter and found that the ravine turned to a sharp angle to the left.

I had reached the bank and stood on a ledge projecting well out, watching my scouts who had crossed and were intently discussing some signs they had discovered, when one of them suddenly ran back and said they had found squaw tracks that had gone out there and thence ran back to the ravine, probably had seen Trimble. Just at this time I saw on the opposite bank of the ravine and about a hundred yards to my left an Indian dog suddenly appear at the top of the ravine, and just as suddenly an arm appeared and snatched the dog out of sight. I then knew that the coveted prize was mine. In the meantime my men lined the bank.

Jack and his family were secreted in a little cave near the top of the ravine and within point blank range of the ledge on which I stood. I told my scouts to ask Jack if he would surrender, and to come out if he desired and give himself up. He replied that he would surrender, but requested time to put on a clean shirt before making his appearance. This I granted and sent word to Trimble to come up and receive him and conduct him back to the crossing where I would join him. I then took Jack and his family back to headquarters and turned him over to General Davis together with his rifles. 1

Thus ended the terrible Modoc War where so many valuable lives were sacrificed, and which I always believed might have been avoided by a little judicious handling of these Indians at the outset.

By Brig.-Gen. David Perry 2 , United States Army (Retired)

Citations:

- It was quite pathetic, during the scout, to discover the means and maneuvers of this small band of fugitives to elude capture. They had with them the infant daughter of the chief, by whose tiny footprints, pattered on the earth, the trailers made sure of their game. While the small party took refuge in the canon and sought to make preparations for further flight, one poor deformed henchman, with devoted loyalty, stood guard upon the height. A small white cloth on which was spread some freshly cured camas root, drying, claimed his attention for a moment, or it may be that the pangs of hunger overcame his watchfulness, for in his moment of inattention he was surprised and captured almost with gun in hand. Now, trembling with fright and unspeakable anguish, he was made to disclose the proximity of his master. who, upon his sentinel’s repeated summons, returned the hail and came forth a captive, to return no more.”- Memorandum by Major Trimble.[

]

- For his gallantry in this campaign Captain Perry was recommended for a well-earned brevet.[

]