There is ample evidence of record, besides that derived from other sources, that the systematic use of gesture speech was of great antiquity. Livy so declares, and Quintilian specifies that the “lex gestus … ab illis temporibus heroicis orta est.” Plato classed its practice among civil virtues, and Chrysippus gave it place among the proper education of freemen. Athenæus tells that gestures were even reduced to distinct classification with appropriate terminology. The class suited to comedy was called Cordax, that to tragedy Eumelia, and that for satire Sicinnis, from the inventor Sicinnus. Bathyllus from these formed a fourth class, adapted to pantomime. This system appears to have been particularly applicable to theatrical performances. Quintilian, later, gave most elaborate rules for gestures in oratory, which are specially noticeable from the importance attached to the manner of disposing the fingers. He attributed to each particular disposition a significance or suitableness which are not now obvious. Some of them are retained by modern orators, but without the same, or indeed any, intentional meaning, and others are wholly disused.

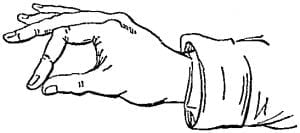

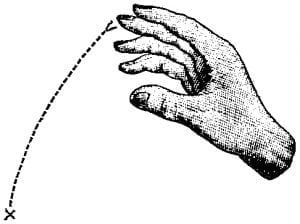

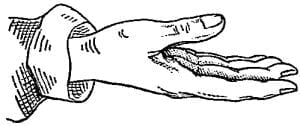

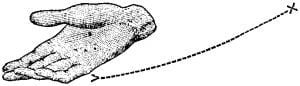

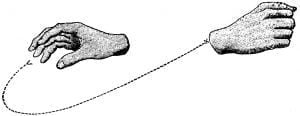

The value of these digital arrangements is, however, shown by their use among the modern Italians, to whom they have directly descended. From many illustrations of this fact the following is selected. Fig. 61 is copied from Austin’s Chironomia as his graphic execution of the gesture described by Quintilian: “The fore finger of the right hand joining the middle of its nail to the extremity of its own thumb, and moderately extending the rest of the fingers, is graceful in approving.” Fig. 62 is taken from De Jorio’s plates and descriptions of the gestures among modern Neapolitans, with the same idea of approbation”good.”

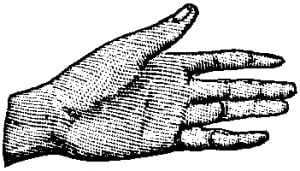

Both of these may be compared with Fig. 63, a common sign among the North American Indians to express affirmation and approbation. With the knowledge of these details it is possible to believe the story of Macrobius that Cicero used to vie with Roscius, the celebrated actor, as to which of them could express a sentiment in the greater variety of ways, the one by gesture and the other by speech, with the apparent result of victory to the actor who was so satisfied with the superiority of his art that he wrote a book on the subject.

Gestures were treated of with still more distinction as connected with pantomimic dances and representations. Æschylus appears to have brought theatrical gesture to a high degree of perfection, but Telestes, a dancer employed by him, introduced the dumb show, a dance without marked dancing steps, and subordinated to motions of the hands, arms, and body, which is dramatic pantomime. He was so great an artist, says Athenæus, that when he represented the Seven before Thebes he rendered every circumstance manifest by his gestures alone. From Greece, or rather from Egypt, the art was brought to Rome, and in the reign of Augustus was the great delight of that Emperor and his friend Mæcenas. Bathyllus, of Alexandria, was the first to introduce it to the Roman public, but he had a dangerous rival in Pylades. The latter was magnificent, pathetic, and affecting, while Bathyllus was gay and sportive. All Rome was split into factions about their respective merits. Athenæus speaks of a distinguished performer of his own time (he died A.D. 194) named Memphis, whom he calls the “dancing philosopher,” because he showed what the Pythagorean philosophy could do by exhibiting in silence everything with stronger evidence than they could who professed to teach the arts of language. In the reign of Nero, a celebrated pantomimist who had heard that the cynic philosopher Demetrius spoke of the art with contempt, prevailed upon him to witness his performance, with the result that the cynic, more and more astonished, at last cried out aloud, “Man, I not only see, but I hear what you do, for to me you appear to speak with your hands!”Lucian, who narrates this in his work De Saltatione, gives another tribute to the talent of, perhaps, the same performer. A barbarian prince of Pontus (the story is told elsewhere of Tyridates, King of Armenia), having come to Rome to do homage to the Emperor Nero, and been taken to see the pantomimes, was asked on his departure by the Emperor what present he would have as a mark of his favor. The barbarian begged that he might have the principal pantomimist, and upon being asked why he made such an odd request, replied that he had many neighbors who spoke such various and discordant languages that he found it difficult to obtain any interpreter who could understand them or explain his commands; but if he had the dancer he could by his assistance easily make himself intelligible to all.

While the general effect of these pantomimes is often mentioned, there remain but few detailed descriptions of them. Apuleius, however, in the tenth book of his Metamorphosis or “Golden Ass,” gives sufficient details of the performance of the Judgment of Paris to show that it strongly resembled the best form of ballet opera known in modern times. These exhibitions were so greatly in favor that, according to Ammianus Marcellinus, there were in Rome in the year 190 six thousand persons devoted to the art, and that when a famine raged they were all kept in the city, though besides all the strangers all the philosophers were forced to leave. Their popularity continued until the sixth century, and it is evident from a decree of Charlemagne that they were not lost, or at least, had been revived in his time. Those of us who have enjoyed the performance of the original Ravel troupe will admit that the art still survives, though not with the magnificence or perfection, especially with reference to serious subjects, which it exhibited in the age of imperial Rome.

Early and prominent among the post-classic works upon gesture is that of the venerable Bede (who flourished A.D. 672-735) De Loquelâ per Gestum Digitorum, sive de Indigitatione. So much discussion had indeed been carried on in reference to the use of signs for the desideratum of a universal mode of communication, which also was designed to be occult and mystic, that Rabelais, in the beginning of the sixteenth century, who, however satirical, never spent his force upon matters of little importance, devotes much attention to it. He makes his English philosopher, Thaumast “The Wonderful” declare, “I will dispute by signs only, without speaking, for the matters are so abstruse, hard, and arduous, that words proceeding from the mouth of man will never be sufficient for unfolding of them to my liking.”

The earliest contributions of practical value connected with the subject were made by George Dalgarno, of Aberdeen, in two works, one published in London, 1661, entitled Ars Signorum, vulgo character universalis et lingua philosophica, and the other printed at Oxford, 1680, entitled, Didascalocophus, or the Deaf and Dumb Man’s Tutor. He spent his life in obscurity, and his works, though he was incidentally mentioned by Leibnitz under the name of “M. Dalgarus,” passed into oblivion. Yet he undoubtedly was the precursor of Bishop Wilkins in his Essay toward a Real Character and a Philosophical Language, published in London, 1668, though indeed the first idea was far older, it having been, as reported by Piso, the wish of Galen that some way might be found out to represent things by such peculiar signs and names as should express their natures. Dalgarno’s ideas respecting the education of the dumb were also of the highest value, and though they were too refined and enlightened to be appreciated at the period when he wrote, they probably were used by Dr. Wallis if not by Sicard. Some of his thoughts should be quoted: “As I think the eye to be as docile as the ear; so neither see I any reason but the hand might be made as tractable an organ as the tongue; and as soon brought to form, if not fair, at least legible characters, as the tongue to imitate and echo back articulate sounds.” A paragraph prophetic of the late success in educating blind deaf-mutes is as follows: “The soul can exert her powers by the ministry of any of the senses: and, therefore, when she is deprived of her principal secretaries, the eye and the ear, then she must be contented with the service of her lackeys and scullions, the other senses; which are no less true and faithful to their mistress than the eye and the ear; but not so quick for dispatch.”

In his division of the modes of “expressing the inward emotions by outward and sensible signs” he relegates to physiology cases “when the internal passions are expressed by such external signs as have a natural connection, by way of cause and effect, with the passion they discover, as laughing, weeping, frowning, &c., and this way of interpretation being common to the brute with man belongs to natural philosophy. And because this goes not far enough to serve the rational soul, therefore, man has invented Sematology.” This he divides into Pneumatology, interpretation by sounds conveyed through the ear; Schematology, by figures to the eye, and Haptology, by mutual contact, skin to skin. Schematology is itself divided into Typology or Grammatology, and Cheirology or Dactylology. The latter embraces “the transient motions of the fingers, which of all other ways of interpretation comes nearest to that of the tongue.”

As a phase in the practice of gestures in lieu of speech must be mentioned the code of the Cistercian monks, who were vowed to silence except in religious exercises. That they might literally observe their vows they were obliged to invent a system of communication by signs, a list of which is given by Leibnitz, but does not show much ingenuity.

A curious description of the speech of the early inhabitants of the world, given by Swedenborg in his Arcana Clestia, published 1749-1756, may be compared with the present exhibitions of deaf-mutes in institutions for their instruction. He says it was not articulate like the vocal speech of our time, but was tacit, being produced not by external respiration, but by internal. They were able to express their meaning by slight motions of the lips and corresponding changes of the face.

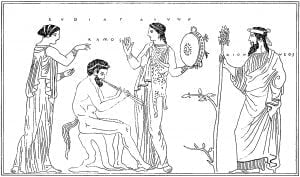

Austin’s comprehensive work, Chironomia, or a Treatise on Rhetorical Delivery, London, 1806, is a repertory of information for all writers on gesture, who have not always given credit to it, as well as on all branches of oratory. This has been freely used by the present writer, as has also the volume by the canon Andrea de Jorio, La Mimica degli Antichi investigata nel Gestire Napoletano, Napoli, 1832. The canon’s chief object was to interpret the gestures of the ancients as shown in their works of art and described in their writings, by the modern gesticulations of the Neapolitans, and he has proved that the general system of gesture once prevailing in ancient Italy is substantially the same as now observed. With an understanding of the existing language of gesture the scenes on the most ancient Greek vases and reliefs obtain a new and interesting significance and form a connecting link between the present and prehistoric times. Two of De Jorio’s plates are here reproduced, Figs. 64 and 67, with such explanation and further illustration as is required for the present subject.

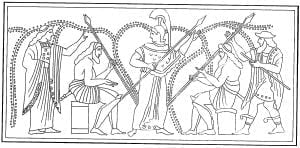

Gestures from a Greek Vase

The spirited figures upon the ancient vase, Fig. 64, are red upon a black ground and are described in the published account in French of the collection of Sir John Coghill, Bart., of which the following is a free translation:

Dionysos or Bacchus is represented with a strong beard, his head girt with the credemnon, clothed in a long folded tunic, above which is an ample cloak, and holding a thyrsus. Under the form of a satyr, Comus, or the genius of the table, plays on the double flute and tries to excite to the dance two nymphs, the companions of BacchusGalené, Tranquility, and Eudia, Serenity. The first of them is dressed in a tunic, above which is a fawn skin, holding a tympanum or classic drum on which she is about to strike, while her companion marks the time by a snapping of the fingers, which custom the author of the catalogue wisely states is still kept up in Italy in the dance of the tarantella. The composition is said to express allegorically that pure and serene pleasures are benefits derived from the god of wine.

This is a fair example of the critical acumen of art-commentators. The gestures of the two nymphs are interesting, but on very slight examination it appears that those of Galené have nothing to do with beat of drum, nor have those of Eudia any connection with music, though it is not so clear what is the true subject under discussion. Aided, however, by the light of the modern sign language of Naples, there seems to be by no means serenity prevailing, but a quarrel between the ladies, on a special subject which is not necessarily pure. The nymph at the reader’s left fixes her eyes upon her companion with her index in the same direction, clearly indicating, thou. That the address is reproachful is shown from her countenance, but with greater certainty from her attitude and the corresponding one of her companion, who raises both her hands in surprise accompanied with negation. The latter is expressed by the right hand raised toward the shoulder, with the palm opposed to the person to whom response is made.

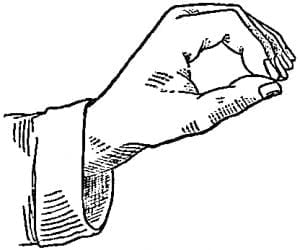

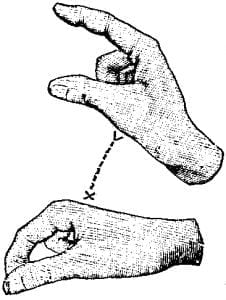

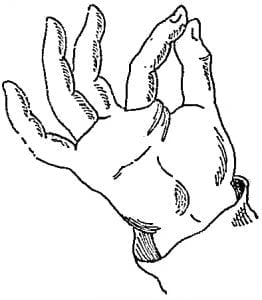

This is the rejection of the idea presented, and is expressed by some of our Indians, as shown in Fig. 65. A sign of the Dakota tribe of Indians with the same signification is given in Fig. 270, page 441, infra. At the same time the upper part of the nymph’s body is drawn backward as far as the preservation of equilibrium permits. So a reproach or accusation is made on the one part, and denied, whether truthfully or not, on the other. Its subject also may be ascertained. The left hand of Eudia is not mute; it is held towards her rival with the balls of the index and thumb united, the modern Neapolitan sign for love, which is drawn more clearly in Fig. 66. It is called the kissing of the thumb and finger, and there is ample authority to show that among the ancient classics it was a sign of marriage. St. Jerome, quoted by Vincenzo Requena, says: “Nam et ipsa digitorum conjunctio, et quasi molli osculo se complectans et fderans, maritum pingit et conjugem;” and Apuleius clearly alludes to the same gesture as used in the adoration of Venus, by the words “primore digito in erectum pollicem residente.” The gesture is one of the few out of the large number described in various parts of Rabelais’ great work, the significance of which is explained. It is made by Naz-de-cabre or Goat’s Nose (Pantagruel, Book III, Ch. XX), who lifted up into the air his left hand, the whole fingers whereof he retained fistways closed together, except the thumb and the forefinger, whose nails he softly joined and coupled to one another. “I understand, quoth Pantagruel, what he meaneth by that sign. It denotes marriage.” The quarrel is thus established to be about love; and the fluting satyr seated between the two nymphs, behind whose back the accusation is furtively made by the jealous one, may well be the object concerning whom jealousy is manifested. Eudia therefore, instead of “serenely” marking time for a “tranquil” tympanist, appears to be crying, “Galené! you bad thing! you are having, or trying to have, an affair with my Comus!”an accusation which this writer verily believes to have been just. The lady’s attitude in affectation of surprised denial is not that of injured innocence.

Gestures from a Vase in the Homeric Gallery

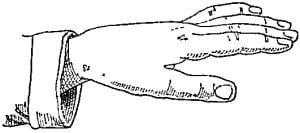

Fig. 67, taken from a vase in the Homeric Gallery, is rich in natural gestures. Without them, from the costumes and attitudes it is easy to recognize the protagonist or principal actor in the group, and its general subject. The warrior goddess Athené stands forth in the midst of what appears to be a council of war. After the study of modern gesture speech, the votes of each member of the council, with the degree of positiveness or interest felt by each, can be ascertained. Athené in animated motion turns her eyes to the right, and extends her left arm and hand to the left, with her right hand brandishing a lance in the same direction, in which her feet show her to be ready to spring.

She is urging the figures on her right to follow her at once to attempt some dangerous enterprise. Of these the elderly man, who is calmly seated, holds his right hand flat and reversed, and suspended slightly above his knee. This probably is the ending of the modern Neapolitan gesture, Fig. 68, which signifies hesitation, advice to pause before hasty action, “go slowly,” and commences higher with a gentle wavering movement downward.

This can be compared with the sign of some of our Indians, Fig. 69, for wait! slowly! The female figure at the left of the group, standing firmly and decidedly, raises her left hand directed to the goddess with the palm vertical. If this is supposed to be a stationary gesture it means, “wait! stop!” It may, however, be the commencement of the last mentioned gesture, “go slow.”

Both of these members of the council advise delay and express doubt of the propriety of immediate action. The sitting warrior on the left of Athené presents his left hand flat and carried well up. This position, supposed to be stationary, now means to ask, inquire, and it may be that he inquires of the othe veteran what reasons he can produce for his temporizing policy. This may be collated with the modern Neapolitan sign for ask, Fig. 70, and the common Indian sign for “tell me!” Fig. 71.

In connection with this it is also interesting to compare the Australian sign for interrogation, Fig. 72, and also the Comanche Indian sign for give me, Fig. 301, page 480, infra. If, however, the artist had the intention to represent the flat hand as in motion from below upward, as is probable from the connection, the meaning is much, greatly. He strongly disapproves the counsel of the opposite side.

Our Indians often express the idea of quantity, much, with the same conception of comparative height, by an upward motion of the extended palm, but with them the palm is held downward. The last figure to the right, by the action of his whole body, shows his rejection of the proposed delay, and his right hand gives the modern sign of combined surprise and reproof.

Gestures in Italian Art

It is interesting to note the similarity of the merely emotional gestures and attitudes of modern Italy with those of the classics. The Pulcinella, Fig. 73, for instance, drawn from life in the streets of Naples, has the same pliancy and abandon of the limbs as appears in the supposed foolish slaves of the Vatican Terence. In close connection with this branch of the study reference must be made to the gestures exhibited in

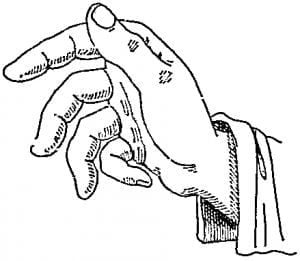

the works of Italian art only modern in comparison with the high antiquity of their predecessors. A good instance is in the Last Supper of Leonardo da Vinci, painted toward the close of the fifteenth century, and to the figure of Judas as there portrayed. The gospel denounces him as a thief, which is expressed in the painting by the hand extended and slightly curved; imitative of the pilferer’s act in clutching and drawing toward him furtively the stolen object, and is the same gesture that now indicates theft in Naples, Fig. 74, and among some of the North American Indians, Fig. 75.

The pictorial propriety of the sign is preserved by the apparent desire of the traitor to obtain the one white loaf of bread on the table (the remainder being of coarser quality) which lies near where his hand is tending. Raffaelle was equally particular in his exhibition of gesture language, even unto the minutest detail of the arrangement of the fingers. It is traditional that he sketched the Madonna’s hands for the Spasimo di Sicilia in eleven different positions before he was satisfied.No allusion to the bibliography of gesture speech, however slight, should close without including the works of Mgr. D. De Haerne, who has, as a member of the Belgian Chamber of Representatives, in addition to his rank in the Roman Catholic Church, been active in promoting the cause of education in general, and especially that of the deaf and dumb.

His admirable treatise The Natural Language of Signs has been translated and is accessible to American readers in the American Annals of the Deaf and Dumb, 1875. In that valuable serial, conducted by Prof. E.A. Fay, of the National Deaf Mute College at Washington, and now in its twenty-sixth volume, a large amount of the current literature on the subject indicated by its title can be found.