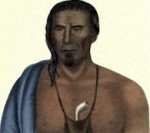

A Delaware Chief

Of Tishcohan, Tasucamin, Teshakomen, alias Tishekunk, little is known, except what is contained in Mr. Fisher and Mr. Tyson’s Report. His name occurs in Heckewelder’s Catalogue, and means, in the Delaware language, “He who never blackens himself” We may note, on referring to the likeness, the correctness of the description, in the absence of those daubs of paint with which the Indian is so fond of deforming himself.

Tasucamin and Lappawinsoe were both signers of the celebrated Walking Purchase of 1737. By this treaty was ceded to the proprietaries of Pennsylvania, an extensive tract of country, stretching along the Delaware, from the Neshamany to far above the Forks at Easton, and westward “as far as a man could walk in a day and a half” This transaction has been stigmatized by Charles Thomson as one of the most nefarious schemes recorded in the colonial annals of Pennsylvania. It appears that the white men, employed to walk with the Indians, performed the task with a celerity of which the Indians loudly complained. They protested against its manner of performance as opposed to the spirit of their contract, and an encroachment on their ancient usages. They alleged that it had been usual, on other occasions, to walk with deliberation, and to rest and smoke by the way, but that the walkers, so called, actually ran, and performed, within the period, a journey of most unreasonable extent.

This purchase has been differently viewed by different writers.

Logan claims the land for the proprietaries, on a two-fold title, independent of the treaty. He claims it under a deed made, in 1686, with the predecessors of the Indians, who asserted a right to it in 1737. He claims it under a release from the Five Nations, in the year 1736, who, at that time, exercised over the Delawares that in solence of superiority which the code of all nations has accorded to conquest. This duple right, the same excellent writer seeks further to confirm and establish, by denying to the Indians, with whom the Walking Treaty was concluded, any original title to the territory ceded, on the ground that they were new settlers from Jersey.

On the other hand, Charles Thomson disputes the antecedent right of the proprietaries, under the deed of 1686, and the release of 1736, and places the whole question upon the honesty with which the stipulations of the contracting parties were performed in the Walking Purchase. And does it not at last repose here? The terms of the original deed are not known. Its authenticity rests only on tradition, and several authoritative legal writers speak dubiously of its ever having existed. One thing is certain, even if it did exist it had never been walked out.

The release from the Five Nations can scarcely be thought to impart validity to a title, which is defective without it. The peculiar subjugation to which the vanquished tribe submitted, could only give to the conquerors the right of personal guardianship, not the power of expatriation. Besides, it is justly contended, that any territorial rights acquired by the Five Nations were confined to the land on the tributaries of the Susquehanna, and never extended to the waters of the Delaware.

We may, therefore, return to the Treaty of 1737, and examine into the manner in which it was executed. If the Indians contracted with had no rights, why was a treaty entertained with them at all ? When the proprietaries entered into a compact with the Indians, they gave to them a right to inquire into the fidelity with which it, was performed, and pledged their own honors for its faithful observance. Was the speed of running a literal or honorable execution of a treaty to walk?

It was this departure from the terms and spirit of the contract which filled the Indians with so much dissatisfaction and heart burning. The execution of the treaty was viewed by them as a piece of knavery and cunning, and concurred with other potent causes of estrangement in bringing about the most unhappy results. The minds of the Indians became alienated, embittered, inflamed; and a perverse and heartless policy, on the part of their white neighbors, made the breach irreconcilable.

But this people, even when goaded to desperation by acts of high handed oppression and cruel selfishness, did not forget the days of William Penn, and were sometimes induced by the recollection, to abstain from visiting upon his successors that degree of retaliation which would have been just, according to their ideas of retributive justice. It was this same people, in the days of their valor and martial glory, that lived on terms of cordiality and friendship with that great man and his followers, in conferring and receiving benefits, for a period of forty years! It was this people so actively kind, so unaffectedly grateful towards the unarmed strangers who sought refuge from persecution in their silent forests, that suffered from the descendants of these strangers, those keen grief arising from a deep sense of unmerited injury, joined to a perception of meditated and the certainty of ultimate annihilation. Contemporaneously with the date of the portraits from which the two foregoing engravings are reduced, the amity and good neighborhood which had subsisted between the colonists of Pennsylvania arid the Delaware Indians, gave way to a state of feeling which ended in the departure of these sons of the soil from their long-enjoyed inheritance, to seek an abode in some distant wild, some inappropriate solitude of the western country. After the indignity they received from Canassatego, in 1742, they retired to Wyoming and Shamokin, and finally penetrated beyond the Ohio, where the survivors live but to brood over their wrongs, and transmit them to their descendants. Pursued from river to river, they at last grew tired of retreat; and, turning back upon their pursuers, inflicted upon them all those cruelties which are prompted by resentment and despair.