In the sketches of other Seminole chiefs, and in the general Indian history, some account of this singular tribe of our aborigines has been given. Halpatter Micco’s history possesses peculiar interest, because he was among the very last few leaders of the fugitive race who were associated with the stirring scenes which transferred the remnant of it to the lands west of the Mississippi.

His father, Secoffer, was an ally of the English, and cherished bitter hostility towards the Spaniards, taking the field against them in the troubles that followed the recession of Florida to their sovereignty. When dying, at the age of seventy, he called to his side his two sons, Payne and Bowlegs, and solemnly charged them to carry out his unfinished plans; and, at any cost, complete the sacrifice of one hundred Spaniards, of which number he had killed eighty-six. This bloody offering, he affirmed, the Great Spirit had required at his hand to open for him the gate of Paradise. We need scarcely add, that such requests were sacredly regarded by the Indians in their uncivilized state. Their fidelity to their vows and treaties was in sad and singular contrast with the faithless dealing of their white invaders.

In 1821, Florida came into the possession of the United States, having within its limits four thousand Seminoles, including the women and children, and eight hundred slaves. The log cabins, environed by cultivated clearings, or grouped together in villages, dotted the country from St. Augustine to Apalachicola River, and attracted the covetous eye of emigrants flocking into the territory.

The Seminoles’ plea of right to the lands by possession had little weight so long as the Government did not recognize the claim.

Two years later, the Indians were pressed into a relinquishment of lands by treaty, and restriction within certain original boundaries. Slaves ran away from white masters, and the Seminoles refused to send them back; property was stolen, and reprisals made; and the occasions of quarrel readily embraced by the settlers, until a sanguinary conflict seemed ready to open its horrors upon the mixed population. Then came the celebrated “Treaty of Payne’s Landing,” made on the 9th of May, 1832, which Mr. Gadsden, commissioned by Secretary Cass, after much difficulty, induced a part of the Seminole chiefs to sign. A delegation was to visit the lands west of the Mississippi, and if the report was favorable, the Florida possessions were to be ceded to the whites, and the removal of the Indians was to follow. In this treaty, the name of Halpatter Micco makes its first appearance in public affairs. A youthful sub-chief of Arpuicki, or “Sam Jones,” he seems to have been bribed or nattered into giving his sign, while Micanopy’s, who was the real head of the nation, and that of other well-known chiefs, were wanting on a document which, in the result, sealed the doom of the Seminoles. Indeed, the delegation repudiated the treaty, and Asseola, a sagacious, crafty, and daring Indian, determined to outgeneral the framers of the instrument. In private life, he nevertheless ruled the councils of the aged Micanopy, and laid a deep plot of resistance to the Government. A negotiation, and a feigned treaty of removal, were used as means of delay, to give time for preparation to make war. It was resolved that if a Seminole sold his property to go west, he should be slain. Months passed by, and as autumn ripened the fields, Charley-e-Mathla, a prominent chief, was waylaid and killed, because he had commenced the sale of his cattle, and the money in his possession forbidden by Asseola to be touched, he declaring that “it was the blood of the red man.” December 28th, 1832, occurred the murder of General Thompson and Lieutenant Smith, as they walked on a sunny afternoon out of the Fort, by Indians in ambush, within sight of the fortress. A larger force was sent to meet Major Dade, who was advancing from Fort Brooke. On the same day that Asseola’s band dispatched General Thompson, this body of savages, numbering one hundred and eighty, fired from behind forest-trees, without a sound of warning, the leaden hail bringing down half of the men at the first fire. Only four privates, out of the eight officers and one hundred and two troops in the ranks, escaped. This was the opening of the Florida war, whose havoc and death cost the nation not less than $40,000,000 and three thousand brave soldiers.

Asseola, who had himself broken treaty, was treacherously betrayed, arid sent to Fort Moultrie to die of broken heart. Coacochu, or Wild Cat, surrendered, and successively bands were scattered, and the remnant of the tribe was driven toward the dark, impassable everglades. In July, 1839, Halpatter Micco made himself conspicuous by a bold and daring exploit to retrieve the falling fortunes of his people. Under an arrangement by Commander Macomb with “Sam Jones,” a leading chief, assigning certain limits beyond which the Indians should not pass, and within which protection should be excluded, Colonel Harney was sent to establish a trading-post. He encamped with thirty men on an open, desolate plain, near the Cooloosahatchee River, and held unsuspecting intercourse daily with the Seminoles. As the dawn of the 22d of July fell on the white tents, Halpatter Micco, at the head of two hundred warriors, rushed upon the sleeping inmates. The surprise was so complete, no resistance was offered. Twenty-four were killed; the rest fled, Harney himself barely escaping by swimming from the river-bank to a fishing-smack anchored in the stream. From this successful raid dates the sudden and growing greatness of the leader, who was soon elevated to the position of principal chief, in place of “Sam Jones,” deposed because of his advanced age and infirmities. The sovereignty was now a narrow one, including not more than two hundred and fifty souls, of whom eighty were warriors. Halpatter Micco saw that the stake was lost, and treaty alone left for his people. He found this was possible, for the United States Government was weary of the terrible struggle, and appeared at headquarters to avail himself of the only hope. The result was, the allotment of a small territory, as a planting and hunting ground, and the announcement, August 14, 1842, that the Florida war was closed.

The peace thus secured continued more than half a score of years, when, in 1856, rumors were abroad that a reopening of the conflict was at hand. Skirmishes followed, and affairs were unsettled for two years. Halpatter Micco, by money, “fire-water,” and ” parley,” was induced to join his brethren in Arkansas. In the spring of 1858 he left his native Florida with thirty-three warriors, eighty women and children, and embarked for New Or leans. ” Sam Jones,” almost a century old, with thirty-eight warriors, refused at any price to leave; the women following the departing chief, ” King Billy,” with shouts of derision, because he had sold his people to the pale faces. He was accompanied by his Lieutenant, Long Jack, a brother-in-law; Ko-Kush-adjo, his Inspector-General, a fine-looking Indian; and Ben-Bruno, his Interpreter and adviser, an intelligent Negro.

At New Orleans he was the “lion” of the day. He illustrated the humiliating fact, that contact with the whites has been destructive to the sobriety of the Indian, and generally demoralizing; an account to be adjusted at the last assize, before an impartial Judge. The libations were freely offered and accepted, until the Seminole Chief was a reeling inebriate in the streets of the Crescent City.

He reached his lands in Arkansas, and, without any notable events in his history, a few years later, died, about fifty years of age.

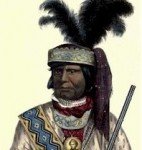

In personal appearance, he was called good-looking. His fore head was broad and high, and under it flashed a sharp black eye, indicating the shrewdness and sly cunning characteristic of the man. His height was above medium, and his person stout, though not corpulent.

His immediate family comprised two wives, one of them comparatively young; six children, of whom five were daughters; and fifty slaves. He had, when he left Florida, a fortune of one hundred thousand dollars. The costume he wore was national and picturesque. On his breast were two medals, bearing the likenesses of Presidents Van Buren and Fillmore.

The name Bowlegs was simply a family cognomen, having no reference to any physical peculiarity. We believe there is no evidence that he renounced his native heathenism, and embraced the gospel of Christ; a sad but not a singular fact, with the lessons of his intercourse with the supplanters of his race.