Rood Creek Mounds (also known as Roods Creek Mounds) is a very large Native American town site in southwestern Georgia that is immediately east of the Chattahoochee River in Stewart County. It was one of the largest Native American towns in the eastern United States. The original palisade enclosed about 120 acres and eight mounds. The final palisade enclosed at least eight mounds and 150 acres. The archaeological zone is now within Rood Landing Recreation Area, a US Army Corps of Engineers facility on Lake Eufaula.

Relatively little is known about this archaeological zone. Four mounds (A, B, D and F) that are the farthest away from the river were briefly studied in 1955 by archaeologist, Joseph Caldwell. In most cases, the examinations consisted of test pits being dug into the mounds. Mound E, the second largest mound that was at the center of the town, was not excavated. This mound has the square, truncated form of a Early Mississippian mound, typical of what is seen at Early Mississippian sites in the Southern Appalachians. (See the section of this article on Architecture.)

There have been no significant archaeological excavations at Rood Creek since 1955.The estimated chronology of the town was based on analysis of pottery styles found on the surface of the site and within those two mounds, without benefit of radiocarbon dating. (See the section of this article on Archaeological studies.)

There has been no professional excavation of the oldest sections of the town site near the Chattahoochee River or of the other six mounds. The unexcavated part of the town composes over 98% of its total area. Inexplicably, academicians have created sophisticated statistical models, based on the tiny percentage of potential artifacts uncovered at Rood Creek Mounds. Contemporary descriptions of Rood Creek Mounds quote Caldwell’s speculations on the town’s western origins as facts applying to the whole site.

Typical of the extrapolation of information from the two mounds to the whole town is the statement in Wikipedia that Rood Creek was a “Middle Mississippian town.” Construction of these two mounds probably began around 1200 AD, but Caldwell placed the original occupation of the soil under the mounds much earlier. He also found artifacts on or near the surface around Mound A that represented all Muskogean cultural periods into the late 1600s or later.

In the book, “The Chattahoochee Chiefdoms” by John H. Blitz and Karl G. Lorenz, the early occupation of the town was described as a “non-mound building period beginning around 1100.” That statement was made without knowing what was contained in the unexcavated 98% of the town area. The authors were anthropology professors at the University of Alabama near Moundville. They sought to link Native towns on the Chattahoochee River with Moundville. Archeologists with the National Park Service have linked artifacts found by Joseph Caldwell to the earliest time period of Ocmulgee, around 900 AD in the Culture & History section of Ocmulgee’s website.

Ethnic Identities of Town Occupants

The founders of Rood Creek Mounds probably originated from the Macon Plateau, Tampa Bay, Lake Okeechobee Basin, Tamaulipas, Mexico or Tabasco, Mexico. More discussion about the origins of Rood Creek can be found in the sections of this report on “Archaeological studies” and “The evidence of a Mesoamerican influence.”

In 1653, Englishman Richard Brigstock visited the Highland Apalache in northern Georgia. Brigstock later told French ethnologist, Charles de Rochefort, that the Apalache originated in the region around Ocmulgee National Monument then occupied the Chattahoochee River Basin. After establishing their capital in the Upper Piedmont of Georgia they claimed to have founded a colony near the Gulf Coast, which eventually evolved a somewhat different language and culture. Those Apalache (Apalachicola) living along the Chattahoochee River continued to be part of the Highland Apalache cultural tradition. This information matches archaeological evidence found by Joseph Caldwell. [For more information see “The Apalache Chronicles” by Marilyn Rae and Richard Thornton – Ancient Cypress Press.]

Analysis of pottery on the upper portions of the mounds by archaeologist Joseph Caldwell indicated that the last occupants of the town were culturally associated with the Apalachicola branch of the Creek Indians. Artifacts in the middle levels often represented stylistic blends between the proto-Muskogeans of Georgia and the Florida Gulf Coast. Earlier phases show cultural affinity with the builders of Ocmulgee National Monument in Macon, GA. However, in the conclusions at the end of his brief report on Rood Creek Mounds, Joseph Caldwell speculated that the original settlers at Rood Creek migrated there from the west.

When Joseph Caldwell was excavating Rood Creek Mounds in 1955 American archaeologists almost universally believed that Cahokia Mounds was the first Mississippian Culture town. They presumed that its advanced culture spread southeastward and southward to sites such as Shiloh Mounds, TN and Moundville, AL then ultimately reached the Macon Plateau. This belief is reflected in Caldwell’s assumption that the Rood Creek Mounds site was settled from the west, probably by people from Moundville or Cahokia.

More precise radiocarbon dating in the past two decades has revealed an exactly opposite chronological situation. Construction of a massive pyramidal mound at the Leake Site on the Etowah River in Georgia began around 0 AD. The oldest Mississippian cultural traits are seen in a cluster of Native American towns around Lake Okeechobee, FL and date from 300-700 AD. The planned town on the Macon Plateau, known as Ocmulgee National Monument, was begun at least as early as 900 AD, but an older settlement has recently been discovered under downtown Macon, across the river.

Initial construction of major mound construction and full manifestation of the Mississippian Culture did not begin at Cahokia for another 150 years, when Ocmulgee had already expanded into a conurbation 12 miles long. Although the Black Warrior River in northwest Alabama was heavily populated by 1100 AD, the earliest platform mounds at Moundville were begun about 200 years after the founding of Ocmulgee.

Chronology of Rood Creek

The Rood Creek Mounds Site at least dates to the earliest manifestations of the Mississippian culture. This is known from the discovery of artifacts typical of Ocmulgee National Monument’s early occupation. In its cultural history of Ocmulgee National Monument, the National Park Service dates the arrival of “Mississippians” at Rood Creek as being contemporary with the Macon Plateau. Given the much greater size of the town in comparison to other towns along the Chattahoochee River, it could well be one of the mother towns of the Chattahoochee Basin.

The very limited examination of four mounds revealed some Woodland style pottery in the sub-mound levels. Since the mounds studies were on the extreme eastern edge of the site, it is likely that more Woodland Period pottery would be found where Joseph Caldwell did not search.

The smaller and land-locked Singer-Moye Mounds site, located several miles to the east, has been more thoroughly studied with late 20th century technology. It was found to have been settled no later than 600 AD, based on radiocarbon dating of organic debitage in its lowest level. Upstream, the Averett Mound Site was found to be first occupied from no later than 880 BC.

Phase I (Swift Creek Culture – Woodland Period ~ 200 BC – 350 AD):

There was probably Swift Creek Culture occupation of the site from around 0 AD until around 350 AD, since both Swift Creek style and Santa Rosa style along the entire length of the Chattahoochee River Valley in Georgia. The Santa Rosa Culture is believed to be a variant or outgrowth of the Swift Creek Culture. Some of the unstudied mounds may are may not belong to the Swift Creek Culture. The Swift Creek People were mound builders and gardeners. Some of their mounds were originally on the scale of later Mississippian Period mounds, but have been eroded and rounded off by up to 2000 years of weather.

Phase II (Weeden Island Culture ~ Woodland Period – 350 AD – 600 AD):

There was probably some habitation of the site between 350 AD and around 550 AD. The largest Weeden Island Culture town was Kolomoki in extreme southwest Georgia. The Weeden Island Culture was a continuation of the Swift Creek Culture in the Gulf Coastal Plain. These people built large mounds, were gardeners and produced ceramics that had a distinct Caribbean or northern South American “flavor” to them.

There was a simultaneous mass abandonment of Swift Creek villages on rivers below the Fall Line somewhere around 550 AD to 600 AD. This corresponds to a period of temporary decline among Maya cities and in the Valley of Mexico. It has been linked to catastrophic volcanic eruptions and a resultant period of reduced sunlight and drought. The abandonments have also been linked to possible invaders or slave raiders. The bow and arrow appeared in the Southeast after the Swift Creek abandonment.

Phase III (Wakulla Culture – Late Woodland Period ~ 600 AD – 900 AD):

Since it is known that settlement began at the nearby, but landlocked, Singer–Moye site around 600 AD or earlier, it is very likely that Rood Creek was also occupied at that time. The Wakulla Culture originated in the Florida Panhandle near the Apalachicola River Basin, which is a continuation of the Chattahoochee-Flint River Basin. People living in Wakulla villages did not normally build large mounds, but had the bow & arrows, plus were farming on a larger scale.

Phase IV (Early Mississippian Period ~ 900 AD – 1200 AD):

At the lowest levels of Mounds A, B and F Joseph Caldwell found undecorated ceramics that were identical to those found at the earliest stages of Ocmulgee Mounds and Hiwassee Island in Tennessee. Archaeologists have labeled this style Ocmulgee Plain Redware. In actuality, this pottery was identical to the Maya Commoner Redware that is endemic in southern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize and Honduras. Maya Commoner Redware is so abundant in the region that it is seldom studied by archaeologists.

In Georgia and Alabama, with the exception of Ocmulgee, Early Mississippian communities typically did not build large mounds. Earthworks typically consisted of relatively clay platforms and small mounds. The first phases of Mounds E and G are prime candidates for being constructed in the Early Mississippian Period. Mound G is closest to the river, while Mound E is the largest mound and in the center of the town.

Phase V (Middle Mississippian Period ~ 1200 AD – 1400 AD):

Contemporary references state that the middle occupation of Rood Creek was culturally tied to Moundville, AL. It is not known what this statement was based on. The town plan is different than Moundville. (See section on Town Plan.) Caldwell reported that most pottery in the middle levels of Mound A’s construction was smooth and undecorated. There frequent use of handles. He stated that it was similar in appearance to Lake Jackson Plain, a type of Mississippian pottery found in the Tallahassee, FL area.

The Middle Mississippian Period ceramics of Rood Creek are also similar to contemporary pottery found on Hiwassee Island and Bussell Island in the Tennessee River. These sites also had early pottery styles that were very similar to the ceramics of the early ceramics at Ocmulgee National Monument. The walls of the ceramic pieces in these provinces were smooth, but they often had decorative rims and handles.

Phase VI (Late Mississippian Period ~ 1400 AD – 1645 AD):

The upper layers of the mounds studied contained numerous potsherds fabricated in the style of the Proto-Creek Lamar Culture, plus the Fort Walton Culture of the eastern Florida Panhandle and the Pinellas Culture of Tampa Bay, FL. In 1955 technology had not been developed to precise determine the specific location that clay had been mined to make pottery. The Florida ceramics may have arrived at Rood Creek via trade or gifts. Five sided mounds continued to be occupied in the Late Mississippian Period along the Lower Chattahoochee River, but in most of Georgia the new mounds were oval shaped.

The 1562 Diego Gutiérrez map of La Florida shows a rather accurate portrayal of the full length of the Chattahoochee River. In fact, the Chattahoochee was the only river on the map whose full length was drawn. Neither the Mississippi nor the Mobile-Alabama-Coosa River system are shown. This feature suggests that an unknown Spanish explorer had traveled to its headwaters at an early date.

In 1645 Spanish authorities in Florida attempted to establish missions on the Lower Chattahoochee River and near the Great Falls, which is now the Columbus-Phenix City area. Most Apalachicola towns were hostile to the missionaries. The Spanish then launched an invasion up the Chattahoochee River which burned many towns. Rood Creek was probably one of them. It was probably abandoned at this time.

Phase VII (Colonial Period ~ 1645 AD – 1776 AD):

Late Lamar Ceramics and artifacts of European manufacture were found by archaeologist Arthur Kelly on or near the surface of Rood Creek Mounds in the early 1950s. It is not clear when these artifacts were deposited. They probably represent the debitage of a small Colonial Period or Federal Period Creek village on the site.

The Spanish established a fort and trading post on the Chattahoochee River’s headwaters in the Nacoochee Valley in 1646. Most of the Apalachicola moved away from the Lower and Middle Chattahoochee River. Some relocated to the Etowah River Valley in northwest Georgia.

In 1717 many branches of the Creeks, Yuchi and Shawnee that formerly lived in eastern Georgia and South Carolina relocated to the Chattahoochee River. The Rood Creek town site was probably reoccupied at this time by a small village or farmstead.

Probable Itza and Chontal Maya Influence

At the time that the Spanish first explored the Gulf Coast region between Mobile Bay and Apalachee Bay it was called Am Ixchel, which are Itza Maya words that mean, “Place of the Goddess Ixchel.” This was also the name of the coastal area of Tamaulipas in northeastern Mexico and the tip of the Yucatan Peninsula. The three regions named Am Ixchel formed a equilateral triangle.

The Chontal Mayas of Tabasco and their neighbors, the Itza Mayas of Chiapas were considered barbarians by the urbanites of Classic Period Maya cities because they were illiterate. However, by 800 AD, these two peoples had come to dominate regional trade in Mesoamerica. The Chontal Mayas were master seafarers who built true boats out of planks. Some were over 60 feet long and had rudders and sails. The Itza Mayas established fortified trading posts at key mountain passes and confluences of rivers and dominated the inland trade.

The language spoken by most Creeks in Georgia, western North Carolina, South Carolina and eastern Tennessee included many borrowed Itza Maya words associated with politics, trade, architecture and agriculture. Many Southeastern Creek descendants have been found to carry some Maya DNA. Some branches of the Cherokees also carry Maya DNA. During the 1500s, 1600s and early 1700s, many Creek towns in the Southern Appalachians and Georgia had pure Maya names.

In 2012 scientists at the University of Minnesota proved that attapulgite from Georgia was used to make Maya Blue pigment and stucco by the Itza Mayas in Chiapas State, Mexico. Chontal Maya seafarers transported the attapulgate from the Chattahoochee River to the coast of Tabasco. The Lower Chattahoochee and Flint River Basin contains the largest attapulgite deposits in the Americas. There is very little attapulgite in southern Mexico. It is probable that Georgia attapulgite was utilized in other Maya regions, but this has not been proven.

Since Chontal Maya cargo boats would have plied the Lower Chattahoochee River for centuries, the similarity of this town’s plan and architecture to Chontal and Itza Maya towns becomes significant. (See “Architecture” below.) Up until around 900 AD, the Chontal and Itza Maya only built earthen mounds. Even then their refined stone structures were primarily limited to the northern Yucatan Peninsula. Elsewhere, they continued primarily to build earthen platforms for wood frame structures.

The Itza Mayas and the Itsate Creeks of Georgia were the only people in the Western Hemisphere who constructed five sided pyramidal mounds such as Mound A at Rood Creek. The Itza Mayas were under the political domination of the Totonacs from around 100 AD to 600 AD. Their town plans and language reflected this influence. Itza contains many Totonac words that are not found in other Maya languages. The Totonacs continued to have a strong cultural influence on them until around 1200 AD. The Georgia Creek word for house is chiki. The Totonac and Itza Maya word for house is chiki.

Town Plan of Rood Creek Mounds

Like Ocmulgee, Shiloh (TN) and Moundville (AL) Rood Creek was situated on a terrace overlooking a large river and fertile bottomlands. In its final form, the footprint of Rood Creek was roughly a non-symmetrical rectangle. Its southwestern, southwestern and northeastern palisades were adjacent to Rood Creek. It is possible that Rood Creek was relocated from its Early Mississippian channel, but this is not known for certain.

The original plan was probably very similar to Ocmulgee’s; a townscape cluster along a linear plaza. Its ultimate town plan, however, was very different than those of most of the indigenous towns in the Southeast. It was distinctly Totonac and Itza Maya in character, yet unlike Maya cities, the population was crowded behind timber walls. Some smaller Maya cities in the Puuc Region of eastern Campeche also had walls and gates, but this was not common elsewhere in the Yucatan.

Totonac and Itza Maya town plans were asymmetrical. Major public structures were interlined by a matrix of small, medium and large plazas. Their towns did not focus on large, rectangular plazas as seen at Cahokia and the Toltec capital of Tula.

The last phase of Rood Creek development involved the creation of a large ellipsoid plaza in its eastern half. All of Joseph Caldwell’s excavations were in this section.. Such plazas are associated with the Lamar Culture in western Georgia, the Georgia Mountains, western North Carolina and eastern Tennessee.

All of these oval plazas are in the region that Creek Indian tradition remembers as the “Ancient kingdom of Apalache.” Like the pentagonal mounds of the Middle Mississippian Period, large oval plazas are very rare outside the original territory of the ancestors of the Creek Indians.

Architecture of Rood Creek Mounds

The platform mounds at Rood Creek are dispersed around the town and each has its own plaza. This is typical of Maya and Totonac cities during the Classic Period of Mexico. There are several types of mounds at Rood Creek that represent all three intervals of the Mississippian Cultural Period. Some of the mounds closer to the river may have bases dating from the Late Woodland Period.

The residential architecture of Rood Creek was not studied by Joseph Caldwell. For the attached illustrations (see photo gallery below), it was assumed that its houses were like those in other towns along the Lower Chattahoochee River. These houses were rectangular. They were erected with prefabricated timber frames set into ditches. After the house was fully framed, about 8-12” of clay was plastered to a sapling lathing. The much largers houses of the elite had 2-3 rooms and were plastered with colorful clays. The roofs of all buildings were either thatched, covered in river canes or finished with bark shingles.

The temples and warehouses of the Proto-Creek Apalache Kingdom in the Piedmont and Coastal Plain were built with the same construction techniques as the houses, only with larger timbers as frames. According to late 16th and 17th century European visitors, some Apalache temples in the Georgia Mountains were built out of fieldstone, mortared or plastered with clay. The temples had much finer quality stucco finishes, however. Many were coated with mica chips, which made them glisten like gold. Others were finished with a mixture of crushed mussel shells, crude lime and white kaolin clay. Still other were finished with red clay stained with red or gold ocher.

The ancestors of the Creeks built two types of large buildings. Warehouses could be up to 200 feet long, but relatively narrow. They had the proportions of modern-day chicken houses. Banquet halls could be up to 50 feet wide and 150 feet long. In order to span such distances, it is probable that the Apalache Creeks understood the basic scientific principles of a roof truss. Interestingly enough, the Mayas were not able to build wood frame buildings of this scale.

Mound A:

This mound is one of several pentagonal mounds found along the Lower Chattahoochee River that were begun in the Middle Mississippian Period, but were later expanded in the Late Mississippian Period. Pentagonal mounds in northern Georgia and western North Carolina typically were not expanded in the Late Mississippian Period. The pentagonal mounds in northern Georgia and western North Carolina are more vertical in proportion than those along the Chattahoochee River.

At the time that Caldwell excavated it, Mound A was 7.6 meters (25 ft) in height, with summit measuring 44.2 meters (145 ft) by 38.1 meters (125 ft). Due to erosion and subsidence of the clay during the past 500 years, the original mound was probably around 9.1 meters (30 feet) in height. The mound was contained at least eight construction levels, each separated by brightly colored sand of varying colors. Evidence of a clay parapet wall was found around the edge of the mound cap. This was probably reinforced by split board planks.

Caldwell found the ruins of three structures on the cap of the mound. Each was about 7.6 meters (25 feet) square. One burial was also found near the cap. The mound was only partially excavated.

The geometry of this pentagonal mound was directly linked to the azimuth of sun. The southwestern facet faced the Winter Solstice Sunset while the western apex pointed toward the Summer Solstice sunset. The northwestern facet was perpendicular to the Winter Solstice sunrise. The southern facet faced the Summer Solstice noon time position. All Middle Mississippian pentagonal mounds outside the Lower Chattahoochee Valley, with the exception of the Kenimer Mound in Nacoochee Valley, were aligned to the Winter Solstice sunset.

Mound B:

This was a small, rectangular mound with rounded corners, about 200 feet west of Mound A. It is 38.1 m (125 ft) long and 18.3 m (60 ft) wide. When seen by Caldwell, it was about 3 meters (10 ft) tall, so was probably about 3.66 m (12 ft) when originally constructed.

Caldwell excavated a small portion of this mound. He found evidence (post holes) that a structure had once sat on the cap, but too little of the mound was excavated to determine its dimensions and shape.

Mound C:

This mound was not studied, measured or discussed by Joseph Caldwell. Mound C is a medium sized oval shaped mound, typical of the Lamar Period. It is similar in size and form to the Nacoochee Mound near Helen, GA and the Peachtree Mound near Murphy, NC.

Mound D:

Very little of this mound was studied. A five feet wide trench, originally begun by an artifact poacher, was continued almost to the center of the mound. The mound was estimated to measure about 24.4 m (80 ft) square and be 2.44 m (8 ft) high. It was probably, originally about 3.66 m (10 ft) high.

The mound was the platform for a building of unknown size. The mound was constructed out of layers of clay and sand.

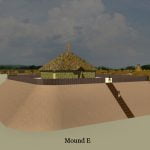

Mound E:

Mound E is the second largest mound at Rood Creek, but was not excavated, measured or described by Caldwell. It is a rectangular pyramid, similar in proportion to Mound A (Great Temple Mound) at Ocmulgee National Monument. The dimensions at the base are about 61 m (200 ft) by 54.9 m (180 ft). The mound was probably, originally about 7.6 m (25 ft) high.

This architecture is typical of the Early Mississippian Period in northern Georgia and western North Carolina. Ocmulgee’s Mound A was begun around 900 AD. Several mounds, built in this form in northern Georgia and western North Carolina, are believed to date from around 1000 AD.

Mound F:

This mound was circular and about 30.5 m (100 ft) in diameter. At the time of excavation it was about 1 meter (3 ft) high. Caldwell presumed that the mound was domiciliary and therefore dug a 3 feet deep pit and stopped. It was more likely the ruins of a chokopa, a communal building. Eight such structures were found at Ocmulgee National Monument. Twentieth century archaeologists called the earth lodges because they were round, but they were not earth lodges. They were conical shaped structures that were structured like a tee pee.

Mound G:

This mound was conical in shape. It was very similar in form to the Great Mortuary Mound at Ocmulgee National Monument. It is around 48.8 m (160 ft) in diameter. Mound G was not excavated, measured or described by Caldwell. Because of its position on the southwest tip of the town, it was most likely a burial mound, but this is not known for certain.

Mound H:

This mound is very similar to Mound F, but was not excavated, measured or described by Caldwell. Like Mound F, it was most likely the base of a chokopa.

Archaeological Studies of Rood Creek Mounds

At the turn of the century, Clarence Bloomfield Moore attempted to excavate the mounds, but was denied access. In the early 1950s, Arthur Kelly, Director of the Department of Anthropology at the University of Georgia walked over the Rood Creek site after it had been plowed. He collected hundreds of potsherds, tools and weapons to analyze.

The announcement of the construction of the Gaines Dam on the Chattahoochee River below Columbus caused local historians to be concerned that the Rood Creek Mounds site would be covered in water before being studied. The Corps was funding archaeological studies near the proposed site of Buford Dam, north of Atlanta, and in the late 1940s had funded a comprehensive archaeological survey of the Allatoona Dam, north of Atlanta. It is not clear, why similar studied were not authorized for what would become Lake Eufaula. Perhaps only surveys were being authorized, not extensive digs.

Several civic leaders in Columbus pooled their funds to hire an archaeologist. Joseph Caldwell was the one selected. At that time, he was a young graduate student. He would not get his PhD from the University of Chicago until 1957. Caldwell’s funding was very limited. Much of the labor of excavation was carried out by volunteers that included soldiers from Fort Benning.

Caldwell expected to return to the site the next year, but shortly after the Rood Creek investigation, he was hired full time to work in a supervisor position at the high profile, Etowah Mounds excavation. From there Caldwell went to the Tugaloo Site near the headwaters of the Savannah River in northeast Georgia. After that project, he devoted much of his time finishing up his doctorate.

The focus of Caldwell’s interest in archaeology was pottery. That is reflected in the brief report that he prepared for the Columbus History Museum. The report spends much of its space on the pottery discovered at Rood Creek and very little on the architecture and town plan. Caldwell was not aware of the astronomical orientations of the mounds or the similarity of the older mounds to Ocmulgee National Monument. He intentionally avoided excavation of house sites.

Ownership and Access to Rood Creek Mounds

Rood Creek Mounds is today located on Lake Eufaula in Stewart County, GA. The archaeological zone today is owned and managed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers as part of the Rood Landing Recreation Area. The ruins can only be viewed in the presence of a ACE ranger by previous appointment.