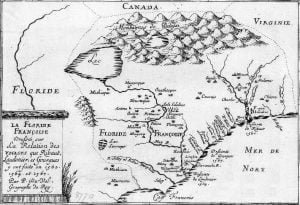

American history textbooks typically provide a cursory chapter on the period of the 16th century Spanish explorers of the Southeast and a few sentences to the attempts of French Huguenots to establish a colony in the region. They jump to the failed attempt to establish an English colony on Roanoke Island, North Carolina, then lavish attention on Jamestown, VA and Plymouth Plantation, Massachusetts. The texts then proceed to describe the founding of the various colonies which became the original United States. Very little, if anything, is said about the French and English explorers who ventured into the interior of the Southeast between 1568 and 1700. University level Colonial History courses might go into more detail on these intrepid people, but the general public in the United States never learns about them. The impression is given that the interior of America was a vast, sparsely inhabited wilderness. Unfortunately, even the textbook discussions of the de Soto and Pardo Expeditions have become tainted by the speculations of late 20th century historians and anthropologists, who didn’t do their homework. Students are told that these two Spaniards passed through “the land of the Cherokees” in the Southern Appalachians. Muskogean town names and political titles are presented as Cherokee words when, in fact, neither the word Cherokee, nor any definite Cherokee village name, was seen on a European map until 1717. Students don’t know any better because they assume that the books are accurate. There is another point of confusion when 19th and 20th century historians analyzed the archives of 16th and 17th century European explorers, the location of Florida. To 16th and 17th century Europeans, the word “Florida” meant all of the present, lower Southeastern United States. That concept really did not change until the colony of Carolina was founded in 1670. Afterward Florida meant all the Spanish controlled land, south of Carolina, but after 1733 south of the Colony of Georgia. Later scholars did not understand the broader meaning of Florida. When they found old texts that discussed the land of Apalachee, where there were mountains, waterfalls and gold, the scholars assumed that the books were fantasies, because everyone knew that there were no mountains or gold deposits in Florida . . . and of course, Florida is where the Apalachee Indians lived.

Narváez Expedition (1528)

In 1528 Don Panfilo de Narváez arrived on the Gulf Coast of Florida near Tampa Bay to explore the region and establish a colony. The expedition was a disaster, but fortunately one of the four survivors, Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, wrote a book on his experiences during the eight years that he was stranded in North America. 1 He tells us that near Tampa Bay, some Natives told him that many days to the north was a people named the Apalache, who had much gold. Contemporary authors consistently replicate the misconception that has lasted for over 450 years. They call the people that the Spanish met near the Suwannee River, Timucuans, and the next people that the Spanish met, Apalachees. Timucuan is the Castilian mispronunciation of Tamakoa. It was a hybrid Totonac-Arawak word, which meant “Trade People,” and only applied to one province near the coast of Georgia. 2 As will be seen in the next paragraph, the Apalachee Indians of the Florida Panhandle never called themselves Apalachee. According to Rochefort, they called the ethnic group in the mountains, Apalache, and called themselves, the Alachua. The word survives in many place names around Tallahassee. There was a village named Apalache and another named Apalachien, in the Florida Panhandle, but their occupants were apparently migrants from the real Apalache. There was also no ethnic group that called themselves the Guale. There was a village on the Georgia coast name Wahale (Southerners) whose Spanish spelling of the word was applied to the portion of the Georgia coast, north of the Altamaha River. Less there be any doubt about the Muskogean-Maya ethnic composition of the Southern Appalachians in the 1500s, the following translations are of the town names visited by de Soto and Pardo, when passing through that region:

- Chiloki (Totonac & Creek) = Barbarians

- Suale (Itsate-Creek) = Buzzard

- Guaxale (Itsate-Creek) = Southerners [Wahale]

- Conasagua (Itsate-Creek) = Hognose Skunk [Konas-Sawa]

- Chiaha (Maya) = Salvia Lord or River

- Conos (Itsate-Creek) = Spotted Skunk

- Cauche (Maya) = Forested Mountains [Kaa’xi]

- Tali (Itsate-Creek) = Stone or Planned Town

- Taske (Itsate-Creek) = Piliated Woodpecker

- Casqui (Koasati) = Warrior; Chiska (Creek) = Aboriginal People

- Chalohuma (Alabama) = Red Fox

- Coça (hybrid Maya-Itsate Creek) = Eagle People [Kaw-se]

- Talimachusee (Creek) = New Planned Town. 3

De Soto Expedition (1540)

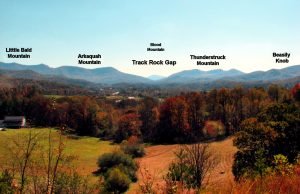

In the late winter of 1540, as Hernando de Soto was heading north out of the Florida Panhandle, he asked the locals where he could find gold. 4 They told him that about two weeks march north were the Snowy Mountains. There lived the Apalache People. They mined gold from the mountains. Their capital was named, Yupaha, and in it was stored much gold. Yupaha is a hybrid Muskogean-Maya word meaning either “Horned Lord,” “Lord of the Horn” or “Horned River.” One cannot be certain because the Spanish did not record the accent marks. The view of the Track Rock Terrace Complex in the Georgia Mountains from the north appears to be a horn rising from a “U” shaped mountain gap. Seventeenth century engravers drew the elite of Apalache to be wearing strange hats that looked single horns. 5 De Soto’s expedition traveled generally north in search of Apalache until reaching the Ocmulgee River, then inexplicably turned east. 6 The word, Yupaha, is never mentioned again. However, after leaving Kusa (Coça) in late August of 1540, he passed through the town of Ubahali. Spanish chroniclers typically portrayed a Muskogean “p” as a “b”. Ubahali was probably Yupahali, which means “Yupaha People” in Coastal Itsate Creek. One of the other strange things that de Soto did was to take a northern loop route from a town named Kofitachiki in southeastern South Carolina to reach Kusa in northwestern Georgia. He bypassed the Georgia Mountains. 7 There was a major trade route, known in the 1700s as the Tugaloo Trail that would have taken him straight to Kusa across the Georgia Mountains. The region that de Soto bypassed happens to be the exact territory described as the Kingdom of Apalache in 17th century texts. Did his Native American guides intentionally lead him around an area that they knew contained many gold deposits? There is no way of knowing today. What is known is that 17th century texts describe a long bloody war between Apalache and Kusa. 8 Perhaps the two provinces were at war in 1540.

French Huguenot Trade Delegations (1564-1565)

After completing the fortifications of Fort Caroline, René de Laundonnière began dispatching small parties to explore the interior and cement trade relations between the French and the region’s inhabitants. 9 Some of the trade delegations were absent for several months. All were received warmly by the inhabitants. The region that was of primary interest to de Laundonnière was the province of Apalache, because of its mineral wealth, fertile soils and temperate climate. De Laundonnière named the Appalachian Mountains in their honor. He planned to build the capital of New France in the foothills of these mountains. The parties went northwestward up the Altamaha River and then in a general northerly direction on the Oconee River, until reaching shallow water that inhibited canoe travel. They then took a trail in a northwestward direction that connected the center of the gold belt to the Oconee. Today that trail is US 129. U. S. Highway 129 will take you through the gold mining center of Dahlonega, over Blood Mountain, near Track Rock Gap, past the mounds of Tamatli in the Andrews Valley, through the silver-bearing Snowbird Mountains then all the way to the Little Tennessee River and Great Smoky Mountains. Here you will be near the probable site of the capital town of Chiaha that was visited by both Hernando de Soto and Juan Pardo. The most successful of the expeditions was led by La Roche Ferriére. 10 From the Appalachian Mountains, he brought back yellow gold, red gold, copper, silver, greenstone, rubies and sapphires. From this information, we know some of the places that he visited. The silver came from the Snowbird Mountains between Murphy, NC, Robbinsville, NC and Nantahala Gorge. The copper came from the Blue Ridge, GA – Copperhill, TN area. The red gold came from eastern Gilmer County, GA. The yellow gold came from the region around Dahlonega, Helen and Gainesville, GA. The high quality greenstone came from near Dahlonega. The rubies and sapphires came from the region between Franklin, NC and Sapphire Valley, NC. Ferriére was not allowed to visit the capital of the Apalache, which was in the higher mountains.

Juan Pardo Expeditions (1567-1569)

Captain Juan Pardo intended to blaze a trade route from Santa Elena on the South Carolina coast to Kusa in present day northwest Georgia. 11 His chronicles do not mention the province of Apalache. Pardo attempted to travel from Chiaha to Kusa (Coça) via a route that would have taken him through the heart of Apalache and even, Track Rock Gap. However, he was warned of an ambush and so turned around to return to Santa Elena on the coast.

Trade contacts between Santa Elena and Apalache (1567-1584)

Relación de Pedro Morales: Sir Francis Drake captured Pedro Morales when he sacked St. Augustine in 1587. 12 Morales had previous lived in Santa Elena and participated in trading expeditions to the Appalachian Mountains. Richard Hakuyt obtained a sworn deposition from Morales, which contained some valuable historical evidence, long overlooked by scholars. Morales began by stating that there were gold and crystal mines in the Apalache Mountains. The nearest range of these mountains was 60 Spanish leagues (168 miles) northwest of Santa Elena. This would actually be the distance to Elberton, GA – about 40 miles from the Blue Ridge Mountains. It is very clear that the Cherokee Indians were not living in the Southern Highlands in the 1560’s. Morales did not mention of any tribe other than the Apalache. Hakluyt quoted the deposition of Morales:

“There is a great Citie, sixteene or twentie dayes journey from Santa Helena, Northwestward, which the Spaniards call La Grand Copal, which they thinke to bee very rich and exceedinglie great, and have been within sighte of it, some of them. They have offered in general to the King to take no wages of all of him, if he will leave to discover this citie, and the rich mountaines around it. He saith also that he have seen a diamonde which was brought from the mountaines that lye west up from S. Helena. These hils seem wholy to be the mountaines of Apalatci, whereof the Savages advertised of Laudonniere, and it may bee they are the hils of Chaunis Temoatam, of which Master Lane had adverstisement of.”

Relación de Nicholas Burgiognon: De Burgiongnon was one of few male occupants of Fort Caroline who was spared. 13 He apparently was a musician in his teens when Fort Caroline was attacked. Sir Francis Drake recorded that Burgiongnon joyfully played a Huguenot march song with his flute as he crossed the Matanzas River to be rescued by the English Protestants. Richard Hakuyt also obtained a deposition from Burgiognon. It contains considerably more information about Spanish trading activities in the mountains. It is very clear from this deposition that many Spaniards traveled to the Georgia and Carolina Mountains. The statement “taking leave at their own costs” means that they were not being chartered by the Spanish Crown. There are no records in the Spanish archives about these journeys. At the end, Burgiognon explained that Spanish officials did not want France and England to know that Spain was exploring and prospecting the Apalache gold fields. Once Great Britain gained control of the eastern half of North America, its leaders were apparently more than happy to completely erase the knowledge that Spain had been exploring, mining and settling the Southern Highlands for 200 years prior to the arrival of the English. Hakluyt wrote:

“He further affirmith that there is a citie Northwestward from Santa Helena in the mountains, which the Spaniards call La Grand Copal, and that in these mountaines there are great store of Christalls, Golde, Rubies and Diamondes : And that a Spaniard brought forth from thence a Diamonde which was worth 5,000 crownes. Pedro Melendes, the marques nephew to old Pedro Melendes that slew Ribault & is now governour of Florida, wear it. He saith also, that to make passage into these mountaines, it is necessary to have a store of Hatchets to give unto the Indians, and a store of Pickaxes to break the mountaines, Which shine so bright in the day in some places, that thy cannot behold them, and therefore they travel unto them by night. Also gortletz of cotton, which Spaniards call Zacopitz, are necessary to bee had, against the arrows of the Savages.” “He saith further that a tone of the sassafras of Florida is solde in Spain for sixtie ducats : and that they have such great store of Turkie cocks, of Beanes, of Pease, and there aqre great store of Pearlses. The things, as he reportith, that the Floridians make most account of, are red Cloth, or redde Cotton to make bandraks or girdles: copper and Hatchets.” “The Spaniards have demaunded leave at their own costs, to discover the mountains, which the King of Spain denyth, for feare let the English or French would enter into the same action, once known. All the Spaniards would passe up by the river of Saint Helena unto the mountaines of Golde and Chrystall. The Spaniards entering 50 leagues from Saint Helena found Indians wearing Golde rings in their nostrils and eares. They also found Oxen, but lesse than ours. “

Hakluyt added:

“Watarin is a river fortie leagues (95 miles) distant Northward of Saint Helena, where any fleete of great ships may ride safely. I take this river to bee the one we call Waren in Virginia, whither at last Christmasse 1585. The Spaniards sent a barke with fortie me to see where we were seated: in this barke was Nicholas Burgiognon the reporter of these things.”

During the 1500’s, both the English and the Spanish used the term “crystal” to refer to precious and semi-precious stones. They considered clear quartz crystals to be semi-precious stones. Burgiongnon claimed that diamonds were found in the mountains. This may reflect a mistaken identity of clear quartz crystals. However, according to an article in a 1902 edition of the New York Times, true diamonds were found by early settlers in Georgia that was formerly the Apalache Province. 14They were definitely diamonds. Some were quite large. The largest diamond bearing zone was in the southern end of the Georgia Gold Belt. The trail used by French Huguenot explorers in 1565 would have crossed the diamond zone. Several large diamonds have been discovered in sediment that washed down from the mountains into the Piedmont or were in mountain streams. The Georgia Mountains were once crossed by a chain of volcanic cones. The largest stone structure archaeological zones in Union County, GA are on the sides of ancient volcanoes that could contain the vent tubes where diamonds were typically created.

French Huguenot Privateers and Colonists (1568 – 1610)

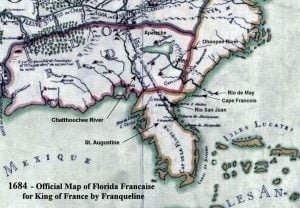

From 1565 until 1763, the Kingdom of France claimed what is now South Carolina, Georgia and western North Carolina, based on the explorations of René de Laundonnière. It was stated so on all French and most Dutch maps. The region was called Florida Françoise. France NEVER claimed the St. Johns River, where Florida historians placed Fort Caroline. All French maps showed Fort Caroline on the Altamaha River in present day Georgia. 15 According to Charles de Rochefort, a mid-17th century French Huguenot explorer and writer, small numbers of French Huguenots continued to travel and settle in the Kingdom of Apalache after 1568. France was in chaos because of the Religious Wars. 16 Transportation would have been provided by the swarms of French Huguenot privateers that preyed on Catholic League merchant ships. The newcomers expanded the colony started by six Frenchmen who survived Fort Caroline. Presumably, they took Native American wives, since there is no mention of female French Huguenots immigrating to the Appalachian Mountains. In 1594, King Henry of Navarre, commander of Protestant forces in France, agreed to convert to Roman Catholicism in order to be crowned King Henry IV of France. After defeating the Catholic League, King Henry issued the Edict of Nantes, which made Roman Catholicism the official state religion, but allowed the Protestants to worship as they preferred. Peace came to France, therefore Huguenot merchants again became interested in colonizing North America. All of the early attempts (some successful) to colonize Canada and Acadia were sponsored by Huguenot merchants, chartered by King Henry. The king did not want to provoke war with Spain by attempting to enforce France’s claim to Florida Françoise. However, the official freedom of movement given French Huguenots enabled them to go elsewhere in private commercial pursuits. That freedom ended with the assassination of King Henry in 1610. Very soon thereafter, all Huguenot merchants and nobility were banned from court. They were increasingly forced to emigrate in order for their businesses to continue.

Spanish Reconnaissance Patrols (1601 – 1628)

Beginning in 1601 the governor of Florida in St. Augustine was repeatedly told by Native American informants that bands of white men had been seen on horseback in the Appalachian Mountains and Piedmont. A young officer, Juan de Lara was sent northward in 1602 to search for more information about the horsemen. 17 The Tamatli and Okute did not allow de Lara to proceed northward. He was told that if any Spanish entered what is now northern Georgia, they would be killed. In subsequent years five reconnaissance patrols were sent northward to search for illegal colonists and were stopped for the same reason. In 1624 and 1628 Ensign Pedro de Torres again went northward to investigate rumors of non-Spanish Europeans in the mountains, but he was also stopped. St. Augustine had a relatively small garrison that was vastly outnumbered by the generally hostile Creek provinces in the Georgia Piedmont.

Spanish Explorers and Missionaries on the Chattahoochee River (1643 – 1646)

In 1643 the Roman Catholic Church sent missionaries up the Chattahoochee River. 18 A permanent mission was attempted near present day Columbus, GA. It was burned. There well could have been temporary mission stations farther north on the river in Native houses. Some natives were converted, but the missionaries were not generally well received by the Apalachicola Creeks. In the winter of 1645-46, Governor Benito Ruíz de Salazar Vallecilla led a group of soldiers north from the Apalachee mission province into the villages of the Apalachicola province along the Chattahoochee River. Several major towns were burned and the mission was rebuilt. Many of the survivors fled northward to the Etowah River in northwest Georgia, where some Apalachicola already lived, and re-established their towns. Apparently, the Apalachicola and the Mountain Apalache were the same ethnic group, or at least, closely related. In the Spanish archives is also the brief mention that Ruíz established a trading post on the headwaters of the Chattahoochee River to serve the Apalache Indians in the mountains. It is not clear if the trading post was below Powers Ferry Shoals in NW Atlanta that traditionally blocked canoe passage, or actually in the Helen, GA area, where the Chattahoochee River begins. Ruiz did more than build a trading post. From that time forward, the Spanish maps of La Florida contained a very accurate description of the Chattahoochee River all the way to its source on the side of Brasstown Bald Mountain. Ruíz had sent engineers or cartographers all the way into the heart of Apalache. Spain claimed the drainage basin of the Chattahoochee from then until 1745, when they lost a war with Great Britain. It is not clear how long the trading post lasted.

Citations:

- Adorno, Rolena; Pautz, Patrick, (1999-09-15). Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca: His Account, His Life, and the Expedition of Panfilo de Narváez, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.[

]

- In fact, Tamakoa, may merely be the Arawak name for the Tamatli, a hybrid Itza-Maya ~ Muskogean people, who dominated the Altamaha River. The memoir of Captain René de Laundonniére, commander of Fort Caroline, places the Tamakoa about 100 miles upstream on the May River from Fort Caroline. Tamatli means “Trade People” in the Itsate-Creek dialect of the Georgia Coastal Plain.[

]

- Thornton, Richard, Ancient Roots V: The Southern Highlands, Volume III, Raleigh: Lulu Publishing Co., 2011; pp. 46 – 50. Words were translated using dictionaries for the Creek, Alabama, Koasati, Totonac & Maya languages.[

]

- Knight, Clayton, et al, The De Soto Chronicles, Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1994.[

]

- Thornton, Richard, Ancient Roots V: The Southern Highlands, Volume III, Raleigh: Lulu Publishing Co., 2011; pp. 46 – 50. Words were translated using dictionaries for the Creek, Alabama, Koasati, Totonac & Maya languages.[

]

- Knight, Clayton, et al, The De Soto Chronicles, Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1994.[

]

- Knight, Clayton, et al, The De Soto Chronicles, Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1994.[

]

- De Rochefort, Charles, Histoire naturelle et moraledes îles Antilles de l’Amérique, Rotterdam: Armout Leers, 1665, “Paysage au Apalache.”[

]

- Bennett, Charles C., Three Voyages, Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001; p. 92.[

]

- Bennett, Charles C., Three Voyages, Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001; p.116.[

]

- Juan de la, Relacion de la Florida, 1569; (Ketchum translation.[

]

- Hakluyt, Richard, The Voyages of René de Laundonnière, The Principal Navigations, Voiages, Traffiques and Discoueries of the English Nation, vol. IX. “The Relation of Pedro Morales,” 1586; p.112.[

]

- Hakluyt, Richard, The Voyages of René de Laundonnière, The Principal Navigations, Voiages, Traffiques and Discoueries of the English Nation, vol. IX. “The Relation of Pedro Morales,” 1586; p.113.[

]

- Wilson, T. Edgar, “Native American Diamonds; The Recent Discovery in Georgia.” March 02, 1902, The New York Times Magazine Supplement, Page SM4.[

]

- Jean Baptiste Franquelin, Carte du Louisiane – 1684.[

]

- De Rochefort, Charles, Histoire naturelle et moraledes îles Antilles de l’Amérique, Rotterdam: Armout Leers, 1665, “Paysage au Apalache.” [

]

- Hudson, Charles, and Tesser, Carmen Chaves, The Forgotten Centuries: Indians and Europeans in the American South, 1521-1704. University of Georgia Press, Athens.1994.[

]

- Tebeau, Charlton, A History of Florida, Rev. Ed. University of Miami Press, 1980.[

]