The night of October 17, 1890, found me a lodger in the railroad station at Laguna.

The day after my arrival I went to the pueblo, which is but a few minutes walk west of the station, and was introduced to the Principal men of Laguna, who, learning the nature of my visit, received me with every expression of respect. The town is built upon a sandstone ledge, the southern base of which is washed by the San Jose. The streets are narrow and winding, and in some places very steep, requiring stone steps. The houses are constructed of stone and adobe, the walls projecting above their flat roofs from 12 to 15 inches. They are kept neat inside and out, and there is a general air of cleanliness throughout the pueblo, no doubt greatly owing to the natural drainage of the sloping sides of its rock foundation. Except the large court where the dances are held, but few of the buildings are more than 1 story high; about the court they are 2, and sometimes 3. The town, conforming to the irregular surface on which it is built, presents a pleasing picture from nearly every point of view outside its walls. The Catholic mission erected in the earlier days of the Spanish rule, occupies the apex, commanding views of a large part of the town far up and down the valley and far to the south beyond the sand hills, where are the mesas She-nat-sa and Tim-me-yah. Near the Mission, in front and a little below, is the schoolhouse, the walls of which resemble the battlements of a mediaeval castle. This old pueblo furnishes the quaintest and drollest of street scenes. There were children in scanty clothing playing with good natured, gaunt looking mongrel dogs and riding young burros, regardless of the dirt and fleas with which their canine companions were covered, and heedless of the uncertain hind legs the otherwise patient and stupid asses possessed; the women glide (almost flit) about attending to their various duties, some bringing ollas of water poised upon their heads from the spring a mile away, and others occupied at the dome shaped ovens, from which they draw forth large, rich looking loaves of bread; groups of old-gossips, men and women, whose usefulness was limited to the caring for their very young grandchildren, who contentedly rested upon the backs of their gray haired elders, securely held there in the folds of variously colored blankets; men going to the fields and coming in with loads of bright corn and dark melons, carried in brightly painted modern wagons drawn by scrubby horses, and in primitive carts pulled along behind sleepy oxen with yokes attached to their horns, Hens and chickens were scratching everywhere for stray kernels of corn, sometimes stealing upon the tempting piles of ears, husked and unhusked that lay about the yards and housetops, only to be driven off by the watchful maidens engaged in husking and storing away. The people of Laguna, as to customs, habits, dances, and ceremonies, are similar to the other New Mexico Pueblos. 1

From the town we walked to the spring, a little more than a mile away. Following the path along and around, the foot of a high hill of lava and volcanic rock, beneath which crops out a sandstone ledge, we came to the fountain, which I was told had never failed in its supply during the most severe droughts, and it had always been the favorite trysting place of the young. The pretty group we found there did not regard our presence as intrusive in the least. Down the smooth sides of the sand rock are deep grooves worn by the children, who use it on pleasant days for the innocent pastime of sliding. We climbed up over this spot to the lava and volcanic rock and to the top of the hill, From the summit I was shown the ancient shores and now fertile bed of the lake that was once there, and from which the pueblo takes its name, Laguna, One morning I rode to the mesa She-nat-sa. It is nearly 3 miles south, between a billowy sea of sand hills and the mesa Tim-me-yah. It was accessible only on the east side. Leaving our horses, we walked up the rather narrow and difficult path, and spent a great part of the forenoon examining and poking about in its ancient ruins. They cover an area of about 10 acres, the entire surface of the mesa. My companion found a copper bracelet, which he gave me, and I was further fortunate in finding a stone ax of considerable size and weight and many pretty pieces of broken pottery. The place was undoubtedly selected as an abode on account of its position and natural defensive strength. This country for many miles about can be seen from any part of the silent mesa. In the days when it was peopled, and the lookout sat in the old watchtower, the marauding Indians of the plains could not approach without being discovered in time to signal the herders to come in with their flocks and the husbandmen to leave the fields. That part of the plain north to the San Jose River was used in those early days for agricultural purposes; the canals and ditches, dug and graded for irrigation, are mostly buried under the sand hills. The sand hills are literally moving from the southwest to the northeast, the changes being noticeable after the high winds that prevail at different times of the year. Remains of the old canals and ditches are constantly coming to light, which must have been buried during centuries. To the south and west the plain gradually rises up to the Tineh and Coyote mesas; on the south, looking far over Laguna, are the beautiful peaks of the San Mateo mountains, which rise over 11,000 feet above the sea, and away to the northeast down the San Jose valley stand the glistening walls of the mesas of the Canyon Cajoe, all affording pleasing views. We descended to our horses, mounted, and reached home just in time to escape a severe sand storm, which began about noon and continued for 2 days.

Several small villages belonging to the Laguna government are Mesita Negra, about 5 miles east; Paguate, 10 miles north; Encinal, 9 miles northwest; Paraje, 6 miles a little north of west; Santa Ana, 4 miles west; Casa Blanco, 6 miles west, and Seama, 8 miles west. The people of these smaller towns, aside from the corn they cultivate, raise abundance of fruit, such as grapes, peaches, plains, and melons. I was told that a great deal of bad feeling existed between Laguna and Acoma on account of a storage reservoir which they had built together for mutual benefit.

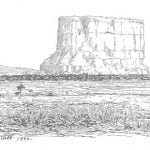

Acoma is but 16 miles from Laguna, and the road by way of Casa Blanco is very good, from which point it leads up a gentle ascent to the upper valley or plain. Reaching the top the first object of interest that attracts the eye is the mesa Encantado, standing in the middle of the plain, its perpendicular walls of red sandstone rising 1,000 feet. Our way lay to the right of this enchanted table rock and through a considerable growth of stunted timber, pine and cedar, beyond which; to the right and left, the mountains rise to great heights and take every form imaginable; gothic spires, towers, domes, and eastern mosques are distributed, one after another, in array. Among the most curious to me were Roca Veutana and Olla (pronounced Ole-ya). All have Spanish names, which the natives use in designating them.

Citations:

- Of the dance at the pueblo of Laguna in 1884, Mr. Lummis, in A Tramp Across the Continent, 1802, pages 101-102, writes:

“Lagoon is the most picturesque of the pueblos that are easily accessible, and, as the railroad runs at the very base of the great dome of rook upon the quaint terraced houses are huddled, there is no difficulty in reaching it. On the summit of the rock is the plaza, or largo public square, surrounded on all sides by the tall house valla and entered only by a narrow alleys. We hastened up the sloping hill by one of the strange footpaths, which the patient feet of 2 centuries grand here worn 8 inches drop in the mild rock, and entered the plaza. It was a remarkable sight. The housetops were brilliant with it gorgeously appareled throng of Indian spectators, watching with breathless interest the strange scene at their foot. Up nod down tho plan’s smooth floor of solid rock then dancers wore leaping, marching, wheeling in perfect rhythm to the wild chant or the chorus nod to the pom, pom of a huge drum, Their faces were weirdly besmeared with vermilion, and upon their heads were war bonnets of eagle feathers, Some carried bows and arrows, some elaborate tomahawks (though that was never a characteristic weapon of the Pueblo Indians), some lances and shields, and it few revolvers and Winchesters. They were stripped to the waist and wore curious shirt of buckskin reaching to the knee, ponderous silver bells, of which some dancers had 2 or 3 apiece, and endless profusion of silver bracelets and rings, silver, turquoise, and coral necklaces and earrings, and sometimes beautifully headed buckskin leggings. The captain or lender had a massive necklace of the terrible claws of the grizzly boar. He was a superb Apollo in bronze, fully 6 feet 3 inches tall, end straight as an arrow. His long, raven hair was done up in it curious wad on the top of his head and stock full of eagle feathers. His leggings were the most elaborate I ever saw, one solid mass behind of elegant beadwork. He curried in his hand a long, steel pointed lance, decorated with many gay colored ribbon’s, and he used this much after the fashion of a drum major.

“When we first arrived upon the scene, and for half an hour thereafter, the dancers were formed in a rectangle, standing 5 abreast and a deep, jumping up and down in a sort of rudimentary clogstep, keeping faultless time and ceaselessly chanting to the ‘music’ of 2 small bass drums. The words were not particularly thrilling, consisting chiefly, it seemed to my untutored ear, of ‘Ho! o-o-o-h! Ho! Ho! Ah! Ho! but the chant was a genuine melody, though different in all ways from any tune you will hear elsewhere, Then the leader gave a yap like a dog and started off over the smooth rock floor, the whole chorus following in single file, leaping high into the air and coming down first on one foot and then on the other, one knee stiff and the other bent, and still singing at the top of their lungs. No matter how high they jumped, they all came down in unison with each other and with the tap of the rude drums. No clog dancer could keep more perfect time to music than do these queer leapers. The evolutions of their ‘grand march’ are too intricate for description, and would completely bewilder a fashionable leader of the german. They wound around in snake-like figurers, now and then falling into a strange but regular groups, never getting confused, never missing a step of their laborious leaping. And such endurance of lung and muscle! They keep up their jumping and shouting all day and all night. During the whole of this serpentine dance the drums and the chorus kept up their clamor, while the leader punctuated the chant by series of wild whoops at regular intervals. All the time, too, while their legs wore busy, their arms were not less so. They kept brandishing aloft their various weapons in a significant style, that ‘would make a man hunt tall grass if he saw them on the plains,’ as Phillips declared, And its for attentive audiences, no American star ever had such a one as that which watched the Christmas dunce at Laguna. Those 800 men, women, and children all stood looking on in decorous silence, never moving a muscle nor uttering is sound. Only once did they relax their gravity, and that was at our coming.

“My nondescript appearance, as I climbed up a house and sat down on the roof, was too much for them, as well it might be.’ The sombrero, with its snakeskin band; the knife and 2 six shooters in my belt; the bulging duck coat, long fringed, snowy leggings; the skunk skin dangling from my blanket roll, and last, but not least, the stuffed coyote over my shoulders, looking natural as life, made up It picture I feel sure they never saw before, and probably never will see. again. They must have thought no Pa-pak-ke-wis, the wild man of the plains. A lot of the children crowded around me, and when I caught the coyote by the neck and shook it, at the same time growling at them savagely, they jumped away, and the whole assembly was convulsed with laughter, For hours we watched the strange, wild spectacle, until the sinking sun warned us to be moving and we reluctantly turned our faces westward.”[

]