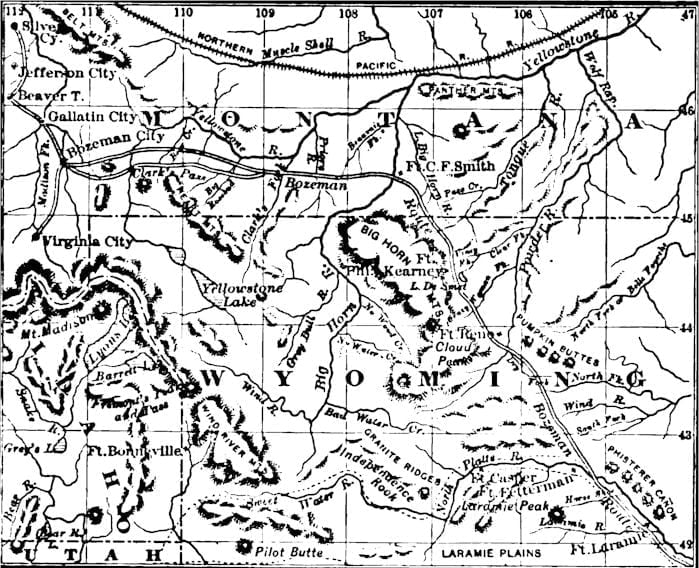

With the resident Indian tribes of Montana the government had treaties of amity previous to the period of gold discovery and settlement. The Blackfoot nation, consisting of four divisions – the Gros Ventre, 1 Piegan, Blood, and Blackfoot proper – occupied the country beginning in the British possessions, bounded on the west by the Rocky Mountains, on the south by a line drawn from Hellgate pass in an easterly direction to the sources of the Musselshell River, and down that stream and the Missouri to the mouth of Milk River, where it was bounded on the east by that stream. To this country, although claimed as their home, they by no means restricted themselves, but wandered, as far as their prowess could defend them, into the territory of the neighboring nations, with which, before the treaty made with I. I. Stevens in 1855, they were always at war. Between themselves they preserved no impassable lines, although the Gros Ventres lived farthest east, and the Piegans along the Missouri River, while the Blackfoot tribe and Bloods domiciled farther north.

Of the four tribes, the Gros Ventres, hitherto the most predatory in their habits, at first appeared the most faithful to their agreement with the United States. Likewise the Piegans, though of the most warlike character, seemed to feel bound by their treaty obligations to refrain from war; while the Blackfoot still occasionally stole the horses of the Flathead; and the Bloods, within ten days after signing the treaty at the mouth of Judith River, set out on a war expedition against the Crows. This nation, which occupied the Gallatin and Yellowstone valleys, with the tributaries of the latter and a portion of the Missouri, was known among other tribes and among fur-hunters and traders as the most mendacious of them all. To out he a Crow, and thereby gain an advantage over him, was the serious study of the mountain men. He was not so good a fighter as the Blackfoot – if he had been, probably he would have had a straighter tongue – but the nation being large, and able to conquer by force of numbers as well as strategy, made him a foe to be dreaded. Of the Blackfoot nation there were 10,000 in 1858, and of the Crows nearly 4,000. The latter, divided into two bands of river and mountain, Crows, had entered into obligations at the treaty of Laramie of 1851, together with other tribes of the plains, to preserve friendly relations with the people of the United States, and were promised annuities from the government in return. These annuities were distributed by Alfred J. Vaughn in the summer of 1854, who made a journey of three hundred miles from Fort Union on the Missouri up the Yellowstone to Port Sarpy, the trading post of P. Choteau Jr & Co., with the goods stored in a keelboat along with the goods of the trading firm. The party was attacked by seventy-five Blackfoot warriors, who killed two out of six Crows accompanying the expedition, and from whom the party escaped only by great exertions. At this distribution the Crows professed adherence to the terms of the Laramie treaty. Vaughn was continued in the office agent to the Crows for several years.

In 1856, the year following the Stevens treaty with the Blackfoot nation, E. A. C. Hatch was a pointed agent to these tribes, but was succeeded by Vaughn in 1867, who, in distributing goods to the Crows the previous year, seemed to have disseminated smallpox; for the disease broke out at this time and carried off 2,000 of them, 1,200 of the Assinaboines, and many of the Arickarees, Gros Ventres, and Mandans. 2 A. H. Redfield was appointed agent for the Crows in 1857, but the mountain Crows avoided assembling at Fort William, at the mouth of the Yellowstone, as directed, and the goods were stored at the fort, which they made a cause of complaint, saying their goods should delivered to them in their own country, on the southern tributaries of the Yellowstone. As they refused the following year to come to Fort William, their agent was compelled to transport two years’ annuities to Fort Sarpy in 1858, as the only apparent means of preserving amicable relations. In the same manner the Bloods refused to come to Fort Benton for their annuities in 1857, and their chief was fain to confess that his young men had been at war with the neighboring tribes and with parties white men.

Although the territory of Montana was divide between the Blackfoot and Crow nations, it was subject to invasion from the west by the Shoshones, now no longer dreaded as an enemy, and from the east by the Sioux, these Arabs of the plains, who roamed from the British possessions to New Mexico, and from Minnesota to the Rocky Mountains. Belonging to the same agency with the Crows were the Assinaboines, of whom there were several bands, in their character resembling the Sioux, yet inferior to them in strength. But of all the tribes, the Sioux were most dreaded and formidable, alike from their numbers, being 13,000 strong, and their warlike character. Their hand was against every man.

No threatening attitude was assumed by the Indians of Montana until the gold discoveries in northern Idaho began, to attract immigration by the Missouri River route. Dissatisfaction was first shown by the Sioux, of whom there were seven different tribes, 3 who attacked Fort Union, in 1850, 400 strong, burning the out-buildings, killing and wounding seven men who were cutting hay, destroying thirty head of cattle and horses, and firing the fort, from which they were with difficulty driven. In 1861 they attempted to burn their agency, but were interrupted by the arrival of troops from Fort Randall, and retired.

In 1864 General Sully pursued the Sioux as far as Montana, and fought them on the Yellowstone, but without the force to achieve an important victory, or even to impress the Indians with awe of his government. In 1865 General Connor met them on Powder River, and punished them more severely for killing immigrants on the Bozeman route just opened. The Blackfoot tribes, agitated by the breath of war, were unsettled and sullen, wishing to fight on one side or the other; and to add to the danger of an outbreak, the Indian country was being filled, not only with licensed traders, but unlicensed whiskey-sellers, whose intercourse with the savages brutalized them, and led to quarrels resulting in murders. Such was the condition of the Indian affairs of Montana when it was organized under a territorial government.

It happened that the Stevens treaty expired 1865, and it was thought a fortunate opportunity renew it, in a different form, and to purchase that part of their country lying south of the Missouri and Teton Rivers. In the mean time, such was the temper of these Indians that Governor Edgerton issued proclamation calling for five hundred volunteers to chastise them, and protect the immigration after arrival at Fort Benton by steamer, and while en route to the mines.

On November 17th a treaty was made with the Blackfoot tribes, by which they relinquished to the United States all their lands except these lying north of latitude 48° and the Teton, Maria, and Missouri Rivers. But the treaty was hardly concluded before these bands, who were not sincere in their promises, resumed depredations, roaming about the country and killing men, horses, and cattle. On the arrival of Secretary Meagher, and upon assuming the executive office in the autumn of 1865, he applied to Major-general Wheaton, commanding at Fort Laramie, for such cavalry as he could spare; but it was pronounced impracticable to march troops into Montana in the winter, and they were promised for the spring. Considerable alarm existing, the acting governor issued a proclamation February 10th, calling for 500 mounted volunteers; but not being able arm, equip, or support in the field such a force, nothing was done beyond pursuing the predatory parties with such means and men as were within reach. An engagement took place March 1st between a band of Bloods and a party of road- viewers at Sun River Bridge, in which James Malone was severely wounds one Indian killed, and three were captured and hanged. About the middle of the summer Colon Reeves, commandant of the upper Missouri, arrived from Fort Rice with 800 well-equipped soldiers under Major William Clinton, and established Camp Cook at the mouth of Judith River.

On the 30th of June 1865, another treaty was arranged. Two thousand Brulés and Ogalallas were in attendance when the council opened, and after two weeks of sending despatches by couriers, the majority of these two tribes came in and signed a treaty, giving their consent to the opening of roads through the territory claimed by them, and were presented with the usual gifts of food, clothing, and ammunition. Red Cloud, however, with several others, held aloof, and the treaty was nothing more than a parley for the purpose of obtaining these same presents and a knowledge of the intentions of the United States.

Military companies had been stationed on the Powder River division of the Bozeman route in 1865 to keep the Indians away; and in May 1866 Colonel H. B. Carrington, who had been made commander of the district of the Mountains, left Fort Kearny with the 18th United States infantry to erect forts on the line of the road, beginning with the abandonment of Fort Reno, erected by General Connor the previous year and the substitution of a new Fort Reno forty miles farther northwest. The force amounted to 700 men only 220 of whom were trained soldiers. 4

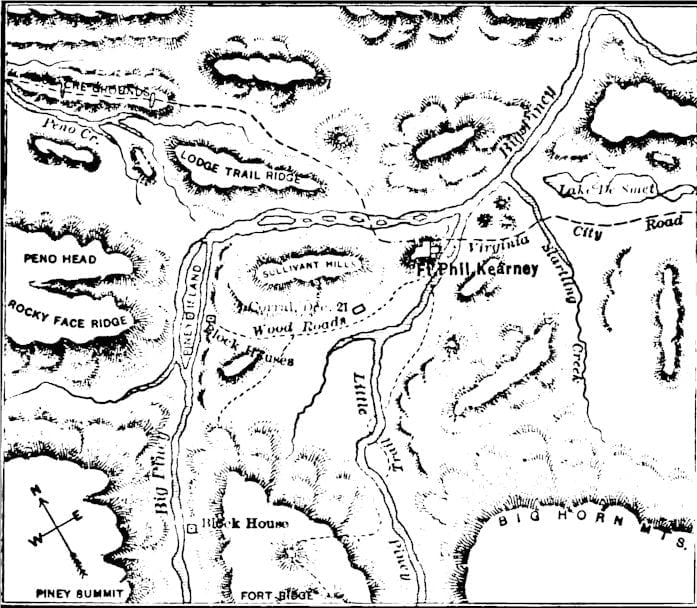

On the 12th of July Carrington arrived at Crazy Woman’s fork of Powder River, where the new Fort Reno was to be located, and where he selects a site, proceeding on his march the next day with two companies, leaving Major Haymond in the rear with the other four. Not far beyond was the proposed site of a fort to be called Philip Kearny, on Piney fork of Clear fork of Powder River, at the eastern base of Bighorn Mountains, where headquarters arrived on the evening of July 13, 1866. On the following day three notable events occurred – the selection of a site for the fort, the desertion of a party of soldiers who had started for the mines, and the arrival of a messenger from the chief Red Cloud declaring war should the commander of the expedition persist in his intention of erecting a fort in the country. Nevertheless, on the 15th the work was begun of constructing the finest military post in the mountains, upon a plan directed by General Crook, which would enable a few men to guard it, leaving the greater part of the garrison to occupy themselves with the protection of the roads, telegraphs, and mails. 5

On the 16th of July Major Haymond arrived and went into camp near headquarters. It was a continued struggle with the command to keep possession of the horses, mules, and cattle, and one in which they were very often beaten. In sorties to recover stock, a number of the men were killed, and nearly all the stock was thus lost.

About the last of August Inspector-general Hazen visited Fort Philip Kearny, and inspired fresh courage by assurances that two companies of regular cavalry had been ordered to re-enforce this post

The Yellowstone post having been given up, Kenney and Burrows with the two companies intended for that service were ordered to construct Fort C. F. Smith, a hundred miles from Fort Philip Kearny, on the Bighorn. In November a part of one of the cavalry companies promised arrived, under Lieutenant Bingham, who proceeded to Fort C. F. Smith, and returned about the 1st of December to Fort Philip Kearny.

Communication had now entirely ceased with C. F, Smith post, for it was no longer safe to travel with an escort of less than fifty men, who could not be spared. Snow was on the ground. A few more trains of logs from the woods were needed to complete quarters which were being built for a fifth company at Port Philip Kearny. The train, when it set out with its teamsters, choppers, and escort, all armed, numbered about ninety men. When two miles from the fort, it was attacked, and signaled for relief. Simultaneously a small party of Indians appeared in sight at the crossing of Big Piney Creek, but were dispersed by shells from the fort. A detail was made at once of fifty men and two officers from the infantry companies, and twenty-six men under Lieutenant Gummond from the 2d cavalry. Colonel Fetterman, at his own request, was given the command of the party, and with him went Captain Brown, also al his own desire, and three citizens experienced in Indian fighting. The orders given by Colonel Carrington were to relieve the wood train, but on no account to pursue the Indians over Lodge Trail Ridge.

Had Fetterman obeyed instructions, the history of Fort Philip Kearny and the Powder River route to Montana would have been vastly different, in all probability. But with a contempt of the danger which the summer’s experience did not justify, he took upon himself a responsibility which cost him his life and the lives of every man and officer who marched with him out of the fort that morning. In less than two hours not a person of the whole eighty-one soldiers and citizens was alive. No report of the engagement was ever made by the living lips of white men, and only the terrible story of the field of death gave any information of what befell the victims.

In January there arrived General H. W. Wessels with two cavalry and four infantry companies, and orders to Carrington to remove headquarters to Fort Casper on the North Platte, and the 18th infantry regiment took its leave of Fort Philip Kearny on the 23d, its connection with the Bozeman route ceasing from that time.

Meanwhile Fort C. F. Smith was invested by hostile Indians to nearly the same extent that its sister fort had been, and even with less opportunities of relief. The only troops in Montana, except the beleaguered ones at that post, being the regiment under Major Clinton at Camp Cook, Governor Meagher addressed that officer, requesting troops to be sent to the Gallatin Valley, to which Clinton replied that he had not the power to assign troops to any station beyond his immediate control. The citizens of Virginia City, however, had not waited for this decision. Mass-meetings were held, and the governor visited Gallatin Valley to procure information. 6

On the 24th of April he issued a proclamation calling for 600 mounted men for three months’ service, during which time it was hoped the government would come to the relief of the territory. Thomas Thoroughman, William Deascey, John S. Slater, John A. Nelson, L. W. Jackson, George W. Hynson, Isaac Evans, and Cornelius Campbell were commissioned to organize companies to serve as Montana militia. Martin Beem 7 was appointed adjutant and inspector-general, with the rank of colonel, Hamilton Cummings 8 quartermaster and commissary-general, with the same rank, and Walter W. De Lacy Engineer-in-chief, with the same rank. On the completion of each company, it was required to march immediately to Bozeman, which had been selected as the rendezvous. The people of Gallatin Valley pledged the subsistence of the troops in the field, and the arming and equipping of the companies was also dependent upon private contribution.

On the organization of companies, Meagher appointed Thomas Thoroughman brigadier-general, with the command of all the troops in the field. Neil Howie 9 was directed to take, with the rank of colonel, the general direction of the troops raised in Lewis and Clarke County. F. X. Beidler, 10 John Fetherstun, James L. Fisk, and Charles Curtis were appointed recruiting officers in the same county, with the rank of captain; and Granville Stuart, Walter B. Dance, and William L. Irwin, recruiting officers, with the rank of captain, in Deer Lodge County. Isaac Evans was appointed captain and assistant quarter-master, Francis C. Deimling was appointed chief of staff, and John D. Hearn 1st aide-de-camp. 11

It was not easy to put 600 troops in the field without a treasury to draw on, but the merchants of Bannack, Helena, and Virginia contributed generously. Wild Indian horses were broken with much labor, and too slowly for the demands of the service, the Helena companies, though first organized, failing to be first in the field for lack of mounts. Captain Hynson’s company left Camp Cummings, at Virginia City, for the Gallatin Valley, 12 about the 1st of May, followed by Captain Lewis and Captain Reuben Foster’s company of scouts, and on the 4th by General Thoroughman. They found the town of Bozeman, which was situated near the entrance of Bridger’s and Jacobs’ passes, at the eastern end of the valley, being enclosed with a stockade. These passes, and one leading out of the valley toward the Blackfoot country, called the Flathead pass, it became the duty of scouts to guard.

On the 7th of May Thoroughman assumed command of the militia, and with Colonel De Lacy set about selecting a suitable site for a fort, with the command of the pass over the Belt or Yellowstone range into the Crow country. The spot selected was eight miles from Bozeman, at the mouth of Rock Canon, where was begun a fortification named Fort Elizabeth Meagher. 13 A picket fort was also established at the Bridger pass. But with the exception of two or three companies, none others appeared upon the ground, the Helena troops disbanding about the last of May because horses could not be procured to mount them.

Just when failure seemed imminent, the energy and acquaintance of Governor Meagher with military affairs prevailed. General Sherman, to whom frequent communications had been sent, at length ordered Colonel William H. Lewis, late commander of Camp Douglas at Salt Lake, to Montana to inquire into the Indian situation, and to ascertain the measure of defense required. The result of the inquiry was that Sherman provided the means of equipping the militia by sending forward the territory’s quota of 2,500 stand of arms, and a twelve-pound battery, with ammunition, and also by telegraphing authority to raise and equip 800 troops to drive out the Indians, until regular soldiers could be sent to take their places.

Shortly afterward there arrived at Bozeman, by unfrequented paths, five refugees, members of an exploring expedition which had wintered at Fort C. F. Smith, who brought intelligence of the deplorable condition of the garrison, which news was confirmed by three deserters who followed. J. M. Bozeman and Thomas Cover started out to learn the true state of affairs, but were attacked, and the former killed. 14

A second attempt was made by forty men under De Lacy, which met with better success. In order to keep watch upon the movements of the Crows and Sioux, the militia was moved forward to the fortified camp, Ida Thoroughman 15 on Shields River, thirty-five miles beyond Fort Meagher, whence reconnoitering parties were kept pretty constantly in motion. 16 The new post was made large enough to held a regiment of cavalry with their horses, and strong enough to resist a siege, with a well, citadel, and every convenience for withstanding one. Thus passed the summer, with no more serious encounters than occasional skirmishes, in which two of the Blackfoot tribe were killed and one Crow hanged.

In the midst of these preparations for defense against a powerful foe, the arrow of death struck down the governing mind, which in shaping and carrying forward military enterprises under great difficulties had won the respect even of his political enemies. On the night of the 1st of July, while en route to Camp Cook on the business of the regiment, General Meagher fell overboard from the steamer G. A. Thompson, then lying at Fort Benton, and was drowned. 17

Governor Green Clay Smith, having returned to Montana about the time of Meagher’s demise and the expiration of the term of enlistment, was ready to assume the command, which he did by making a call for 800 men, and reorganizing the troops under the regulations of the army, with the title of First Regiment of Montana Volunteers. 18 He directed that Thoroughman should retain his headquarters in the Gallatin Valley, whence he would send out from time to time such forces as were necessary to chastise marauding bands, to expedite which Major Howie was ordered to take Captain Hereford’s company, with one section of artillery, and move down the Musselshell River about one hundred miles, where he would establish a camp for the protection of miners and settlers.

After some fighting, with losses on both sides, and further manipulation of troops, regular and volunteer, came the intelligence that the Indian question, except so far as guarding the roads was concerned, was to be left in the hands of the interior department, where it had been placed by congress, and that this department had appointed a peace commission similar to that of the foregoing summer. 19 Two points were named for assembling the Indians, the first at Fort Laramie, September 15th, and the second at Fort Larned, Kansas, October 15th. Runners were sent out to invite all the tribes of the military departments in which these posts were situated, and all military operations were suspended while the negotiations were in progress. In accordance with these regulations, General Terry ordered the mustering out of the volunteers, and they were disbanded about the last of the month, when two companies of regulars were stationed at Bozeman for the protection of the Gallatin Valley, whose commander, Captain R. S. La Motte, founded Fort Ellis, a three-company post, beautifully situated, about two miles and a half from Bozeman. The cost of the volunteer organization was no less than $1,100,000, which charges were referred to congress for payment; and the ‘necessary expenses’ were ordered paid in 1870; but on investigation of charges, the amount was cut down $513,000 in 1873, and that amount paid.

When the legislature met in November, Governor Smith urged the enactment of an efficient militia law, which that body failing to do, the governor, in January, issued a general order for the organization of two military districts within the territory, numbered I. and II, with Brigadier-general Neil Howie in command of the first, and Brigadier-general Andrew J. Snyder in command of the second. 20 The governor’s action was precautionary merely, at this time, yet he had business for the militia before the winter was over, the citizens of Prickly Pear Valley, among others, appealing for arms in February 1868 to protect themselves against the Blackfoot and Blood tribes, who, as territorial critics pithily remarked, had been supplied with murderous weapons by the officers of the government at Benton to make attacks upon white people, whom the peace commissioners recommended should be prohibited from defending themselves. Arms and ammunition were sent to Prickly Pear Valley by order of the executive, and in defiance of the peace commissioners. 21

A treaty was concluded with the mountain Crows May 7th at Fort Laramie, and ratified July 9th, 22 by which they relinquished all claim to any territory except that included between longitude 107° on the east, the Missouri River on the west, latitude 45° on the south, and the Yellowstone River on the north. The Missouri River Crows, Gros Ventres, and Blackfoot tribes were also treated with in July, and the latter ceded, as in 1865, all that portion of their territory lying south of the Missouri and Teton Rivers, reserving all of Montana north of these rivers. Immediate steps were taken by their special agent to establish agencies and carry out the provisions of the treaties. But congress failed, as it so often did, to ratify at the proper time the contracts it had empowered commissioners to make, and to which the Indians had consented, which delay furnished a sufficient provocation, in their minds, to a renewal of hostilities.

All through the spring and summer of 1869 these outrages continued, culminating August 18th in the killing of one of Montana’s oldest and most esteemed citizens, Malcolm Clark. His residence was in the Prickly Pear Valley, and from his long association with the Indian tribes no harm to him was apprehended. Still, a young Piegan, whom he had brought up in his own house, under a pretence of delivering horses stolen by his people, enticed Clark’s son Horace from their dwelling, and shot and wounded him; and on the father going out to speak to a chief, he was shot and killed. Twenty other Piegans were in company with the treacherous Blackfoot, and the lives of Clark’s wife and daughter were saved only by the intervention of an Indian woman.

It was impossible that a mere handful of troops should protect so extensive a frontier as Montana possessed. On the Idaho side the Sheepeaters, under the hostile chief Tendoy, disturbed the peace of the inhabitants. In the Flathead country signs of war were accumulating, through the reservation troubles. 23

The Blackfoot nation was openly at war; the Crows, while professedly friendly, took horses and scalps when convenient; and Red Cloud with several thousand Sioux was encamped on the Bighorn; while the United States troops under General Sheridan were driving the hostel tribes of Kansas and Nebraska northward to swell the forces that at any time could be precipitated upon the territory.

At length a change seemed about to occur. General De Trobriand, in command of the district of Montana, made such representations at Washington as procured more troops in Montana. General Sherman authorized General Sheridan to punish the Piegans, and Sheridan sent his Inspector General James A. Hardie, to Montana to satisfy himself of their guilt.

About the middle of December an expedition was organized, consisting of detachments from the cavalry and a company of mounted infantry, in all between 300 and 400 troops, to invade the Blackfoot country. On the 23d of January 1870, they surprised the Piegan camp on Maria River, killing 173 men, women, and children, and capturing 100. Three hundred horses were captured, and all the winter supplies of forty-four lodges, driving the Blackfoot tribe into the British possessions. 24

On the 1st of March, 1872, congress set apart a tract of land in Montana and Wyoming, fifty-five by sixty-five miles square, about the head of the Yellowstone River, to be called the Yellowstone National Park, and the survey begun in 1871 by Hayden was continued this year in the Gallatin and upper Yellowstone valleys – from the east fork of the Yellowstone to the mining district on Clarke fork; in the Geyser basins, and on Madison River. 25 This survey was not in the route of the raiding Sioux, and escaped any conflict with the common enemy. But a railroad surveying expedition of 300 men under Colonel E. Baker was attacked near the mouth of Pryor fork by a larger number of Sioux and Cheyennes, losing one man killed, and having five wounded. The fighting lasted for several hours, and the Indians, though armed with repeating rifles, lost heavily in men and horses. 26 More fortunate was a pleasure excursion projected by Durfee and Peck of the North-western Transportation Company, which thus early invited travel over the route pursued by them from Chicago westward. The excursionists took boats, built for the occasion, at Sioux City, and proceeded up the Missouri and the Yellowstone as far as Powder River, where a wagon-train was fitted up, and escorted by a strong military guard and reliable guides to Yellowstone park. General Sheridan detailed General Gibbon to accompany this notable excursion – the first purely pleasure-seeking company to visit the nation’s reserve. 27

In the spring of 1873 the Blackfoot tribe, having partially recovered from the humiliation inflicted by Bakers command, became once more troublesome, when the irrepressible conflict was resumed, being carried over the boundary into the British possessions, and returning to the territory of the United States. These raids and skirmishes seldom gave occasion for the employment of the few troops stationed n the territory, but were met and fought by citizens. 28

Citations:

- This tribe claim to have come from the far north, and to have travelled over a large body of ice, which broke up and prevented their return. They then journeyed in a southeast course as far as the Arapahoe country, and remained with that people one year, after which they travelled eastward to the Sioux country, met and fought the Sioux, who drove them back until they fell in with the Piegans, and joined them in a war on the Bloods, after which they remained in the country between the Milk and Missouri Rivers E. A.C. Hatch, in Ind. Aff. Rept, 1856, 75; Dunn’s Hist. Or., l56, 322-3.[↩]

- The Indians like all the dark-skinned races, have a great susceptibility to contagion. In 1838 smallpox carried off 10,000 of the Crow, Blackfoot, Mandan, and Minataree nations. De Smet’s Western Missions, 197.[↩]

- The Brulés, Blackfoot Sioux, Sans Arc, Minnecongies, Uncpapas, Two-kettles, and Yanctonais.[↩]

- Absaraka is the title of a narrative by the wife of one of the officers of the Carrington expedition.[↩]

- Fort Philip Kearny occupied a natural plateau 600 or 800 feet high, with sloping sides or glacis. The stockade was of pine, hewn to a touching surface pointed, and loop holed. At diagonally opposite corners were block-houses of 18 inch pine logs. The parade-ground was 400 feet square with a street 20 feet wide bordering it. East of the fort, taking in Little Piney, was a corral stock, hay, wood, etc., with a palisade 10 feet high, and quarters for teamsters and citizen employees – 12 double cabins, wagon-shop, blacksmith shop, a stables. Room was allowed for 4 companies of infantry. Army and Navy Journal, Nov. 24, 1866.[↩]

- The call for the first mass-meeting was signed by John P. Bruce, W. L. McMath, E. T. Yager, Charles Ohle, P. A. Largy, Marx & Heidenheimer, F. R. Merk, William Deascey, H. L. Hirschfield, John M. Clarkson, J. Feldberg, D. C. Farwell, George Cohn, Henry N. Blake, A. Leech, F. C. Dimling, T. C. Everts, Hez. L. Hosmer, James Gibson, A. M. S. Carpenter, J. J. Hull, William Y. Lovell, E. S. Calhoun, John S. Rockfellow, William H. Chiles, S. E. Vawter, Alphenso Lambrecht, P. S. Pfouts, G. Crow, L. Daems, H. W. Stafford, Martin Beem, N. J. Davis.[↩]

- Beem was from Alton, Illinois. He entered the army as a private, and was promoted to captain.[↩]

- John A. Creighton succeeded him, but resigned, and J. J. Hull was appointed, who was succeeded by Henry N. Blake. John Kingley was major of the regiment.[↩]

- Howie was advanced to the rank of brigadier-general.[↩]

- Beidler was commissioned Lieutenant-colonel[↩]

- Frank Davis was afterward appointed aide-de-camp.[↩]

- Hynson was promoted to be colonel of the 1st Regiment.[↩]

- This appears to have been only a temporary stockade, though dignified by the name of fort.[↩]

- Bozeman is described as ‘a tall, good-natured, good-looking Georgian, with easy habits and a benign countenance.’[↩]

- Named after a daughter of General Thoroughman.[↩]

- The command consisted at this time of the following companies of Montana cavalry: A, Capt and brevet Col George W. Hynson; B, Capt. Robert Hughes; C, Capt 1. H. Evans; D, Capt. Charles F. D. Curtis; E, Capt. Cornelius Campbell; and F, Capt. John A. Nelson. Virginia Montana Post, June 29, 1869. A company was organized at Salmon River, in Idaho, and joined the Montana militia about the last of June, under A. F. Weston Capt, Thomas Bums 1st Lieut, and Charles H. Husted 2d Lieut. Id., June 22, 1867. James Dunleavy was surgeon. I regret not having a complete report of the adjutant-generals, from which to give a more perfect list of officers. I have been compelled to rely wholly on newspaper files.[↩]

- Thomas Francis Meagher was a native of Ireland, and was a natural as well as trained orator. He became a patriot under O’Connell, and was arrested and transported for life. He renounced his parole and escaped from Van Dieman’s Land, arriving in New York in 1852, where he started the Irish News. He afterward went to Central America, and from there wrote articles for Harper’s Magazine. Returning to the U. S., he enlisted in support of the union, and in command of his Irish brigade won laurels, and the title of general. In Montana he provoked much criticism by certain reckless habits, and by an imperious and often wrong-headed political course; bat when it came to military matters he was in his element, and won the gratitude of all. Every respect was paid to his memory, though the body was not recovered.[↩]

- Thomas Thoroughman retained the command, with the rank of Col; George W. Hynson Lieut-Col; Neil Howie 1st major; J. H. Kingley 2d Major.

Company commanders:A, Capt. L. M. Lyda;

B, Capt. Robert Hughes;

C, Capt. Charles J. D. Curtis;

D, Capt. I. H. Evans;

E, Capt. Cornelius Campbell;

F, Capt. John A. Nelson;

G, Capt. A. F. Weston;

I, Capt. Robert Hereford;

K, Capt. William Deascey.Commissions issued by Meagher other than these confirmed by him were made complimentary. Smith’s staff consisted of

Martin Beem Adjutant and Inspector General,

Hamilton Cummings Quarter Master General,

J. J. Hull Commander General, each with the rank of Colonel.[↩] - N. G. Taylor, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, John B. Henderson, chairman of the committee on Indian Affairs in the senate, John B. Sanborn, and S. F. Tappan, constituted the committee; $300,000 was appropriated to subsist friendly Indians, and $150,000 for other expenses. If the commission should fail, the U. S. would accept 4,000 volunteers into the regular service.[↩]

- Howie’s district comprised the counties of Lewis and Clarke, Choteau, Deer Lodge, Missoula, and Meagher, with headquarters at Helena; and Snyder’s district the counties of Madison, Beaverhead, Gallatin, Bighorn, and Jefferson, with headquarters at Virginia City. The generals were ordered to organize their districts into not more than four regiments of eight companies each; the companies to consist of forty enrolled men, who should elect their captain and two lieutenants. The regimental officers were ordered to consist of a colonel, lieutenant colonel, and major, the colonel to be appointed by the district commander, and the lieutenant-colonel and major elected by the line-officers; the colonel to appoint an adjutant from the line with the rank of 1st lieutenant; staff-officers to be appointed, the adjutant with the rank of major, the quartermaster and commissary-general with the rank of Captain, 2 aides-de-camp with the rank of captain, and 1 surgeon with the rank of major. The staff of the commander-in-chief consisted of Moses Veale, adjutant-general, with the rank of brigadier; Hamilton Cummings, quartermaster-general, with the rank of colonel; George W. Hill, commissary-general, with the rank of colonel; L. Daems, M. D., medical director, with the rank of colonel; James H. Mills, J. W. Brown, and W. F. Scribner, aides-de-camp, with the rank of colonel.[↩]

- I represent here the sentiment of the people of the territories. It was said, no doubt with much truth, that the persons interested in peace commissions made fortunes out of these negotiations; that traders flocked to the council grounds, who sold ammunition and arms to the Indians. Two tons of lead and powder were sold at the council of 1866 at Laramie. The Indians expended a year’s collection of furs and robes in war supplies, took all the government offered them in presents, and departed to renew their outrages. These occasions were fairs or markets at which the savages laid in supplies.[↩]

- A treaty was made with the Crows in 1860, at Fort Union, by Gov. Edmunds, Gen. Curtis, and others, by which they yielded to the government the right of a public road through the Yellowstone Valley, and ceded a tract 10 miles square at each station necessary on the route, but the treaty was never ratified. Ind, Aff. Rept, 1868, 223.[↩]

- In June 1855 I. I. Stevens made a treaty with the Flathead, Kootenai, and Pend d’Oreille tribes, whereby they were allowed a general reservation of 5,000 square miles on the Jocko River. To this they all agreed in council; but before signing the treaty the Flatheads demanded an additional reservation in the Bitterroot Valley, embracing 500 or 600 square miles. To this demand Stevens yielded in the 11th article of the treaty, which was ratified in 1859, so far as to say if in the judgment of the president it should be better adapted to the wants of the tribe than the general reservation, then such portions as might be necessary should be set apart to them. White settlers were encouraged by the Indians to settle on this tract, embracing all of the valley above Lolo fork, a beautiful and productive region. The discovery of gold accelerated settlement, to which the Indians made no objection until 1867, at which time the disturbances east of the mountains and in Idaho and eastern Oregon undoubtedly excited their wild natures. That year the citizens of Missoula County petitioned the governor for arms and ammunition, representing that the Flatheads were making threats of driving out all the white people, and had already murdered 4 prospectors between Flathead Lake and Thompson River, had stolen stock, broken into houses, and burned off the grass, the fires consuming the farmers’ hay-stacks. Virginia Montana Post, Oct 5, 1867. War, however, did not follow. The majority of the tribe were on the Jocko reservation, and of these in the Bitterroot Valley some had farms and were on good terms with their white neighbors. More, however, were roving in their habits. These latter, more than the former, were dissatisfied with the occupancy of the white farmers, and talked about claiming a reservation in the valley, to which the neglect of the government to survey and examine the country gave color. In 1869 Gen. Alfred Sully was appointed to the superintendency of Montana, and alarmed the settlers by pro

Easing a new treaty, which would deprive over 200 settlers of their farms. But of this be thought better, when the citizens memorialized the senate of the United States not to confirm the treaty, and gave their reasons. Ind. Aff. Rept. 1869, 26. The citizens did not ask that these Indians who cultivated, and were permanent, should be removed, but suggested that they be allowed to retain a certain amount which the government should patent to them, and General Sully made such a recommendation, coupled with a suggestion to pay the Indians something for removal; and in 1871 the president ordered them to go upon the Jocko reservation, congress having appropriated $30,000 to compensate them for any loss. At length a special commissioner, James A. Garfield, was appointed in 1872 to visit and accomplish the adjustment of the claims of the Flatheads. Investigation showed them to be firm in their impression that the treaty of 1855 gave them the Bitterroot Valley. The Catholic fathers were called on to aid in persuading them to remove, except such as were willing to abandon tribal relations, and to become owners m severalty of their farms. An agreement was finally entered into between the commissioner and the chiefs of the Flathead tribe, that the government should erect 60 houses 12 by 16 feet, 3 of them, for the chiefs, being double the size, and placed wherever on the Jocko reservation they should select, provided the same was not already occupied; they were to be supplied with flour, potatoes, and vegetables the first year; land was to be enclosed and broken up for their use; $55,000 was to be paid to them in installments. Any who chose could take land in Bitterroot Valley under the land laws. On the part of the Flatheads, they agreed to remove all who did not take land in this manner to the Jocko reservation. The following year, however, they refused to remove, basing their refusal on the non-fulfillment of the government’s part of treaty stipulations. A few were prevailed upon to go to the reservation in 1874, more followed, and by degrees the condition of these Indians on their reservation has improved. A boarding school for girls and day school for boys was established by the Catholics of St Ignatius mission, in 1863, discontinued after 13 months because results did not warrant the expense. It was resumed by the government, which paid $1,800 for teachers until 1872, and $2,100 until 1874, when the schools were again closed, and again reopened. Helena Independent, May 15, 1874; Meagher, in Harper’s Magazine, Oct. 1867, 681-3; Winser’s N. Pac. R. R. Guide, 196-7; Smalley’s Hist. N. Pac R. R., 343.[↩]

- This expedition was officered by Col E. M. Baker, commander; Maj. Lewis Thompson, Capt. S. H. Norton, 1st Lieut J. G. McAdams, G. C. Doane, S. T. Hamilton, and S. M. Swigert, and 2d Lieut J. E. Batchelder, 2d cavalry. The infantry was commanded by Lieut-Col George H. Higbee, with Capt. R. A. Surry and 1st Lieut W. M. Waterbury. New Northwest, Feb. 4, 1870.[↩]

- Hayden’s report for 1872 is interesting reading. It makes, with the scientific and technical descriptions, a volume of over 800 pages, and is a survey not only of Montana, but of Idaho, Wyoming, and Utah. In 1877 Hayden made an exhaustive survey of Idaho and Wyoming.[↩]

- It is said that the camp was saved by the promptness and gallantry of Lieut W. J. Reed of the 7tn infantry, who was a Californian before be entered the army. S, F. Alta, Oct. 5, 1872.[↩]

- On the 27th of September Gen. Gibbon lectured at Helena upon the wonders and attractions of this region. Helena Rocky Mountain Gazette, Sept. 30, 1872.[↩]

- Battle of the Little Bighorn.[↩]